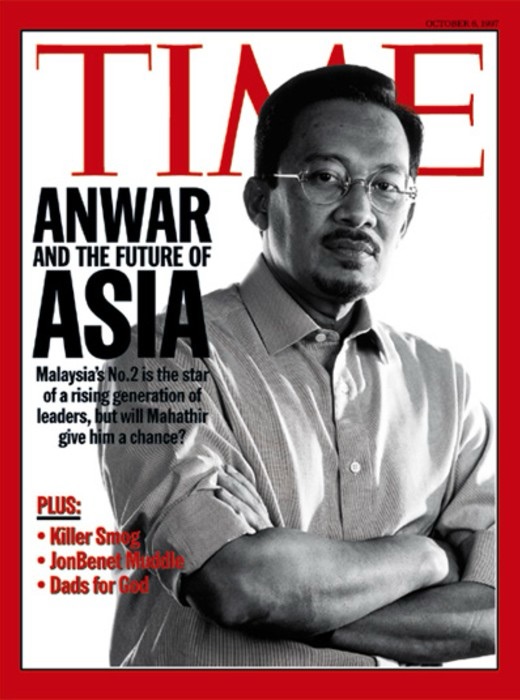

Time Magazine cover, October 6, 1997: Anwar Ibrahim, then Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister, featured with the headline “Anwar and the Future of Asia.”

Malaysia today faces an unusual contradiction.

On the surface, we are told the economy is recovering. Investment is flowing. Subsidies are being rationalised. The GST debate is over. A medium-term revenue strategy is in motion. And inflation, we are assured, remains contained.

But underneath this well-rehearsed narrative, a deeper anxiety simmers. Business leaders are cautious. Civil servants are frustrated. Investors are confused. The rakyat, particularly the urban middle and lower-income households, feel poorer despite all official assurances to the contrary.

And at the heart of that disconnect lies a fundamental question:

Who exactly is responsible for the economy, and where are they taking it?

Global Headwinds but Local Agency Matters More

Yes, global conditions are tough.

Geopolitical fragmentation, prolonged high interest rates, supply chain realignments, and new waves of industrial policy from Washington to Brussels have all reshaped the global trade order. Malaysia is not immune. Nor is any small, open economy.

But let us not pretend that our current economic condition is purely the result of global tides.

Growth is now consistently trailing pre-pandemic trends. Real wages have barely moved. Household debt remains among the highest in Asia. Our fiscal position is tightening not because of a sudden crisis, but due to long-standing policy deferrals and structural complacency.

This is not external fate. This is internal design.

The Data Does Not Lie, But It Does Accuse

Based on official data released by Bank Negara Malaysia and the Department of Statistics, Malaysia’s federal government debt at end-2024 stood at RM 1.1725 trillion. The country’s GDP for the same year was RM 1.6503 trillion.

This puts our debt-to-GDP ratio at 71.05 percent, well above the statutory ceiling of 65 percent as mandated by the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2023.

This is not a speculative concern. It is a factual, legal breach.

Section 4 of the Act sets the ceiling. Section 10 mandates disclosure to Parliament and submission of a fiscal recovery plan if breached. Neither has taken place.

Beyond debt figures, other structural signals are flashing amber. Real wage growth remains tepid. Median household income has stagnated. Budget deficits have exceeded 5 percent of GDP for several consecutive years. FDI inflows remain uneven. Malaysia’s export competitiveness is under renewed threat as global supply chains recalibrate and tariffs loom on the horizon.

These are not isolated metrics. They represent a structural erosion of economic resilience.

A Government of Two Minds

Within this administration, there is a growing tension between two conflicting economic impulses.

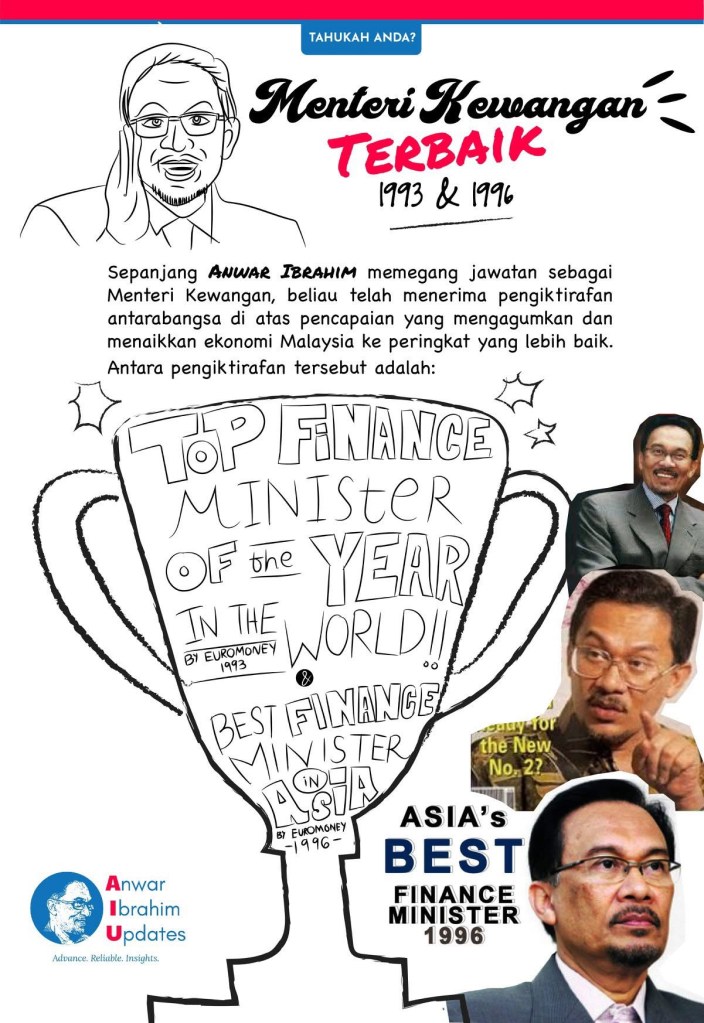

Infographic celebrating Anwar Ibrahim’s tenure as Malaysia’s Finance Minister, highlighting accolades received in 1993 and 1996 including “Top Finance Minister of the Year” by Euromoney and “Asia’s Best Finance Minister” by Asiamoney.

The first is rooted in Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s legacy as a 1990s reformer. It privileges fiscal discipline, macroeconomic credibility, and technocratic rule-based governance. This impulse recalls the Anwar who, during the Asian Financial Crisis, embraced a form of fiscal restraint that mirrored IMF conditionality, albeit without IMF involvement.

The second impulse is populist and reactive. It prioritises visible relief measures over long-term structural shifts. It maintains fuel subsidies, expands social spending, and introduces selective tax exemptions with minimal targeting. These measures are often politically expedient but economically incoherent.

The result is a confused hybrid. Diesel subsidies are cut, but apples and oranges are exempted from tax. SST is expanded to professional services, yet revenue measures are not accompanied by a broader tax reform agenda.

What emerges is neither technocratic clarity nor populist certainty. Instead, we see the contours of drift.

At some point, governments must match institutional authority with political accountability.

This is not a legacy crisis inherited from past administrations. The Fiscal Responsibility Act was tabled, debated, and passed by the current government. The appointments to key ministries were made by the current Prime Minister. The budget, subsidies, and fiscal projections were approved under his direct authority.

Power has been centralised. So must responsibility.

A government cannot consolidate executive control and then plead operational constraints when results fall short.

The PKR State: Who Holds the Commanding Heights

Using the British concept of the commanding heights, a term that refers to strategic sectors that shape national economic direction, the picture in Malaysia is unambiguous.

Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) now holds or controls the three most powerful economic levers in government.

First, the Ministry of Finance, held by the Prime Minister himself.

Second, the Ministry of Economy, entrusted to a technocrat personally appointed by the Prime Minister.

Third, the Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry, led by a trusted PKR affiliate and Anwar ally.

These three ministries determine where capital flows, which industries rise, who gets taxed and who gets exempted, how government-linked companies are governed, and where Malaysia positions itself within the global economy.

This is not just policy centralised. This is power held tightly.

More Than Ministries: Who Controls the Crown Jewels

In addition to these economic super-ministries, three of the country’s most powerful economic institutions are also directly answerable to Anwar.

PETRONAS, the national oil company and single largest contributor to government revenue.

Khazanah Nasional, the country’s sovereign wealth fund.

Permodalan Nasional Berhad, the institutional guardian of Bumiputera capital ownership.

Together, these six nodes comprising three ministries and three national institutions define the architecture of Malaysia’s modern economy. Never before has so much institutional power over money, capital, and economic direction been concentrated under the personalised authority of a single Prime Minister.

And so the question must be asked, not as a political jab but as a matter of governance and strategic capacity:

Can one man, even a long in the tooth veteran like Anwar, truly manage it all – even via his chosen surrogates?

The Debt Breach: A Crisis of Credibility

Let us now turn to the fiscal fundamentals.

As outlined earlier, Malaysia’s federal debt has breached the statutory ceiling by over 6 percentage points. This is not an academic violation. It is a statutory breach of a law passed just 18 months ago by this very government.

Section 10 of the Act requires the Finance Minister to notify Parliament and present a recovery plan. As of now, no such report has been filed. No such plan has been disclosed. No such transparency has been attempted.

The Risk of Institutional Paralysis

We now face a dangerous institutional moment.

The government writes a law. The government breaks that law. The government delays admitting it. And the institutions around it, including the civil service, Parliament, and financial regulators, go silent.

This is not a crisis of fiscal numbers. It is a crisis of fiscal accountability.

If laws passed by Parliament are quietly breached and then retroactively justified, the entire framework of public governance is weakened.

Malaysia deserves better than compliance theatre. Parliament reconvenes in a week. Who will hold Putrajaya to account?

All Roads Lead to Anwar but Where Is He

This brings us to the most difficult but essential point.

If Anwar Ibrahim holds the Finance portfolio, leads the political party that dominates the economic ministries, and appoints the heads of PETRONAS, Khazanah, and PNB, then the economic buck stops with him.

And yet, he is nowhere near the helm.

His attention is increasingly diverted by a string of foreign trips and summits, personal judicial entanglements including a landmark immunity hearing scheduled for 21 July, and endless rounds of party-political signalling, while PKR itself struggles to define its governing identity.

He has time for media interviews and crowd rallies, but not for a formal statement to Parliament on a breach of fiscal law.

He has time to exempt fruit from SST, but not to account for why fiscal discipline collapsed under his watch.

Conclusion: The Leadership Void

Malaysia does not lack economic talent.

Malaysia does not lack institutions.

Malaysia does not even lack plans.

What it lacks is clear economic leadership.

Until that changes, until the Prime Minister chooses to lead the economy rather than outsource it, distract from it, or delay difficult choices, the risk is not simply fiscal. It is systemic.

And if he will not lead it, someone else eventually will.

But not before things get much worse.

Footnote:

For those less familiar with fiscal policy, here is why the debt to GDP breach matters — and why it is not just academic:

📉 1. Borrowing headroom is now constrained

With civil service salaries and pensions absorbing most of the operating budget, any fiscal squeeze lands hardest on development spending. This means roads, railways, schools and digital infrastructure are often the first to be delayed or cancelled. These are the projects that stall.

⏳ 2. Delays in payments to suppliers

When liquidity tightens, ministries begin to defer payments — whether for IT systems, medical equipment or engineering works. Multi month arrears to private sector vendors disrupt cash flow and echo through the entire supply chain.

📆 3. Greater use of deferred procurement structures

To avoid recording large debts upfront, the government turns to alternative arrangements such as build lease transfer (BLT) and public private partnerships (PPP) schemes. These stretch payments over 10 to 30 years, deferring the financial burden but constraining future budgets.

💸 4. Higher taxes and stricter enforcement are likely

To close the gap, the government will turn to revenue measures. Expect broader service tax coverage or new taxes such as carbon pricing or capital gains. The reintroduction of the GST is no longer unthinkable. Enforcement will also tighten — with more audits and more aggressive collections by the tax authorities and Customs.

🔍 5. More tax audits and penalties, even for GLCs.

The revenue crunch has already triggered back assessments across corporate Malaysia. Tenaga Nasional and PETRONAS were among the first. No company is immune. Enforcement is now part of fiscal strategy.

📊 Bottom line

A breach of the Fiscal Responsibility Act is not a legal footnote. It is a structural constraint that reshapes policy, reallocates risk, and sends signals far beyond the numbers. The real economy will feel the consequences.

One response to “The Pied Piper Of Putrajaya”

Thank You for stating the bare truth. However painful it is to swallow, the truth must be told. Everything starts with the Leadership, it sets the tone from the Top. Leadership at home, at school, on the playing field, in Associations, Companies……and the seat of Government!

LikeLike