-

Justice Without Finality

Malaysia has crossed a line that many countries speak of, but few ever do. A former Prime Minister has been investigated, charged, tried, convicted, sentenced, imprisoned, and now sentenced again. Whatever one’s political sympathies, it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge that this alone places Malaysia in a small and serious category of constitutional democracies willing to test their own commitments to the rule of law at the highest level.

The early prosecutions arising from the 1MDB and SRC affairs were widely regarded as lawful, orthodox, and necessary. The first SRC conviction in particular was seen, both domestically and abroad, as a model of judicial discipline. It demonstrated that power did not immunise wrongdoing, and that institutions, when pressed, could still function. That moment mattered, and it deserved recognition.

What has unfolded since is more complex. Over several years, five criminal cases were pursued, involving numerous charges, overlapping factual narratives, and recurring questions of power, control, and responsibility. Two resulted in convictions on all charges, namely the SRC RM42 million case and the 1MDB–Tanore trial, while one ended in acquittal after full trial. Another concluded with a discharge not amounting to an acquittal, one remains pending after repeated postponements, and it is only when these outcomes are placed side by side, over time, that the cumulative shape of punishment comes into view.

The issue that now confronts us is not whether the law acted. It clearly did. The harder question is whether the law, when applied cumulatively over time, still knows how to remain proportionate, intelligible, and human.

In every common law system, sentencing is guided by a principle often referred to as totality. It is not a technicality. It is a recognition that punishment must ultimately speak as one coherent response to a course of wrongdoing, rather than as an arithmetical accumulation of lawful outcomes. Totality exists to prevent a legal system from arriving, step by lawful step, at a result that no single decision maker ever consciously chose.

Historically, Malaysian courts have understood this well. Where multiple offences arise from the same scheme or abuse of office, sentences are folded, adjusted, or moderated so that the final outcome reflects the whole rather than the parts. Even where separate criminal projects exist, restraint has been the norm. Severity was never avoided, but it was bounded by an instinct for closure.

It is against this background that the recent Tanore sentencing has unsettled many within the legal community. The sentence was explicit in its structure. It was ordered to run consecutively to an existing custodial term. It imposed a substantial term of imprisonment, an extraordinary financial penalty, and a lengthy default sentence in the event of non payment. Nothing in the language of the decision suggested consolidation, overlap, or a final act of juridical closure.

This is not a comment on motive, nor an insinuation of bad faith. It is simply an observation about architecture. For the first time in a major Malaysian corruption case, punishment was framed not as a culmination, but as an addition, layered onto what had already been imposed, with little regard to the overall shape that was emerging.

When viewed in isolation, the Tanore sentence can be defended as forceful denunciation. When viewed in context, alongside prior convictions and existing custodial terms, it raises a more difficult question. Taken together, the sequence of custodial terms and default sentences now in place points towards a period of incarceration extending well beyond what would ordinarily be regarded as a working horizon of life.

This is not a uniquely Malaysian question. Courts across the Commonwealth have wrestled with it in cases involving organised crime, terrorism, and large scale fraud. The prevailing instinct in those jurisdictions has been to ensure that even the most severe punishment remains legible. Not because wrongdoing is minimised, but because the law is expected to retain a sense of finality. A sentence that necessarily extends beyond any realistic human lifespan, arrived at through accumulation rather than explicit intention, is treated with caution.

From this comparative perspective, what now invites reflection is not whether Malaysia has been too harsh, but whether it has paused long enough to ask what the final sentence is meant to say. Punishment is not only about denunciation and deterrence. It is also about signalling that the law, having spoken, knows when it has said enough.

There is, inevitably, a human dimension to this. Not one that excuses misconduct, but one that recognises that even the gravest accountability must eventually arrive at a point of conclusion. A legal system that continues to add, without ever consolidating, risks shifting from judgment to attrition, even if every step along the way is lawful.

This is where the role of an apex court becomes central. Not as a saviour, and not as a corrector of facts, but as a steward of coherence. The function of a Federal Court in any common law system is to ensure that justice, in the aggregate, still makes sense. That sentences, however severe, remain proportionate to the totality of wrongdoing rather than the sum of its procedural parts.

Malaysia has already demonstrated that no one is above the law. That achievement should not be diminished. The question now is whether the law can also demonstrate that it knows how to conclude. Not to forgive, not to forget, but to bring judgment to a form that is firm, final, and intelligible.

That is not a political question. It is a jurisprudential one. And it is a question that serious legal systems eventually have to answer.

-

Malaysia’s Bargain with America

A trade agreement that preserved survival, constrained sovereignty, and quietly reshaped the foundations of our political economy

Malaysia’s new trade agreement with the United States was signed to preserve survival, yet its clauses reach far beyond tariffs and exports. It binds us into America’s orbit abroad while quietly reshaping the levers of our political economy at home. History may record it less as a trade pact than as a bargain that altered Malaysia’s future options.

The Context: Trump’s Tariff Shock

In April 2025 President Trump imposed a blanket nineteen percent “reciprocal tariff” on imports from multiple countries. For Malaysia this was not a theoretical threat, since electronics and electrical products make up more than one third of our exports to the U.S., ranging from semiconductors and components to precision parts manufactured in Penang, Johor and Selangor. A tariff of that size would have priced us out of American supply chains almost overnight.

The choice was stark. We could negotiate or suffer. Vietnam and Thailand chose to sign framework agreements that bought them time, while Cambodia, heavily dependent on garment exports, signed quickly to preserve survival. Malaysia, deeply exposed in electronics and engineering, could not afford delay, and hence we signed a hard agreement.What the United States Secured

The agreement delivers a number of trophies that President Trump can now claim as victories at home.

PETRONAS must purchase approximately USD 3.4 billion of U.S. LNG annually, providing a fixed and recurring demand that anchors American energy exports into Asia.

Malaysia also committed to facilitate around USD 70 billion in job-creating investment in the U.S. over the next ten years. Few trade agreements require a developing country to create jobs abroad rather than at home, yet this one does.

In addition, Malaysia agreed not to ban or quota rare earth and mineral exports to the U.S., and guaranteed no restrictions on rare-earth magnets, thereby assuring American supply-chain access in a sector otherwise dominated by China.

Regulatory alignment was also embedded. Malaysia must fast-track halal certification for U.S. food products, accept U.S. FDA approvals for pharmaceuticals and medical devices, and recognise U.S. auto standards. Restrictions on U.S. broadcasting content are lifted, and American digital services cannot face discriminatory treatment.

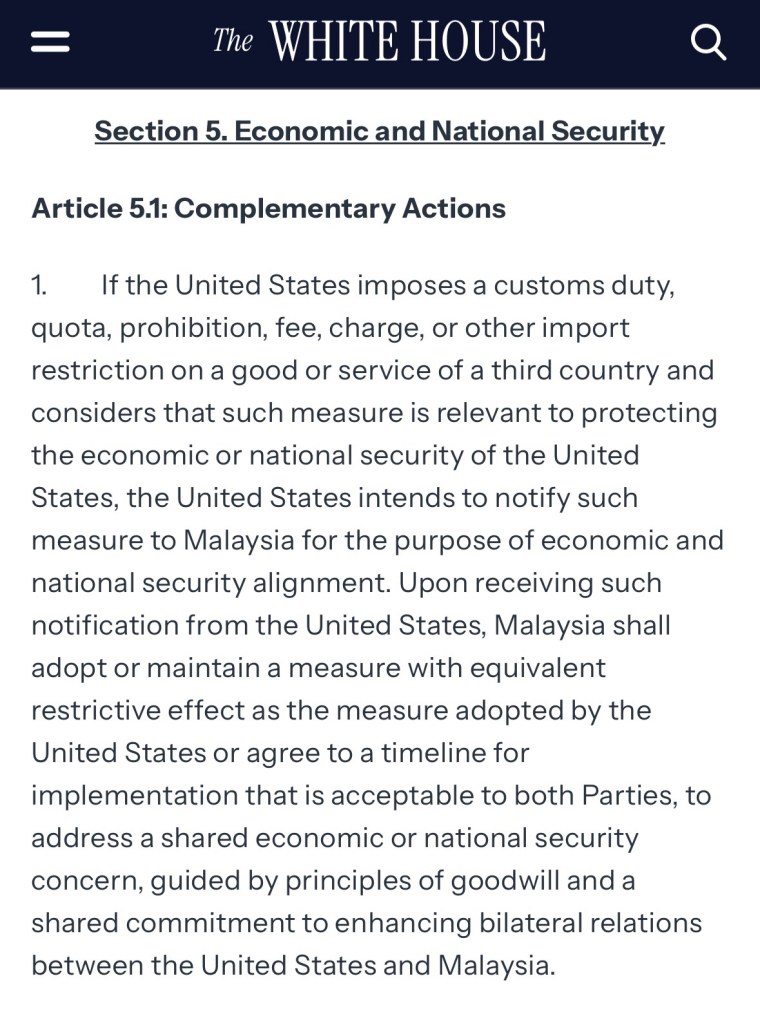

Most significantly, the agreement contains clauses that reach beyond trade. Malaysia must consult the U.S. before entering new digital trade agreements with other countries that might be judged to jeopardise American interests. Malaysia is required to adopt or maintain measures equivalent to U.S. trade restrictions when imposed against third countries. If Malaysia signs a free trade or preferential deal with a country that threatens U.S. interests, Washington may terminate this agreement and reimpose tariffs. These are not commercial provisions alone. They embed Malaysia inside the strategic orbit of the United States.What Malaysia Preserved

To dismiss Malaysia’s position as weakness alone would be unfair, since there were important defensive wins.

By signing, Malaysia ensured its electronics and engineering exports remained competitive in U.S. supply chains, protecting tens of thousands of jobs. A signed agreement also reassures global investors that Malaysia remains a reliable node in the semiconductor and technology ecosystem.

If PETRONAS embraces the challenge of portfolio LNG trading, juggling multiple supply sources and shipping arbitrage, it could emerge stronger in the long term. Most importantly, Malaysia avoided the worst outcome. In any negotiation with Trump there are only two outcomes. He wins and we lose, or he wins and we also win. Malaysia avoided the first of these.

However we need to be clear-eyed and honest about who exactly are the winners and losers both within and beyond Malaysia, and equally about the likely winners and losers in the years ahead as this agreement is enforced.The Strategic Price Paid

Survival came at a cost.

Malaysia now carries binding obligations on LNG imports and outward investment flows. At a time when our own economy needs capital, significant sums have instead been committed to creating jobs in America.

More serious is the narrowing of our sovereign space. Consultation requirements limit our freedom to enter digital trade deals independently. Obligations to mirror U.S. trade measures tie us to American sanctions and disputes with third countries. The termination clause places Malaysia’s future free trade agreements under a U.S. veto threat. Commitments on critical minerals guarantee American access and weaken Malaysia’s leverage in resource diplomacy. Regulatory alignment narrows our room to strike alternative models with China, ASEAN or the Middle East.

The regional dimension also matters. By signing hard during the ASEAN Summit while Thailand and Vietnam kept their options open, Malaysia fractured the symmetry of ASEAN bargaining. Washington now points to Malaysia as precedent, asking other states: “They agreed – why not you?”

Finally, there is the risk of over-payment. If Thailand and Indonesia later conclude softer deals, avoiding LNG obligations, resisting sanction clauses and retaining digital autonomy, Malaysia will look like the country that conceded more and did so too early.A Quiet Reset of the Bumiputra Agenda

Beyond sovereignty, the agreement also reshapes the space in which Malaysia’s race-based economic architecture has long operated. Since the 1970s, Bumiputra-first policies have relied on licensing discretion, regulatory gatekeeping, and preferential access to contracts. By embedding obligations on standards, certification, digital services and market entry into an international treaty, much of that discretion is now constrained.

Malaysia cannot easily reinstate protectionist barriers without triggering treaty violations. Halal approvals must be streamlined. Foreign certificates must be recognised. U.S. digital and broadcasting firms must be given equal treatment. Critical minerals must remain open to American partners. These provisions may appear technical, but together they erode the very levers through which the old order sustained itself.

This is not the abolition of Bumiputra policy. It remains entrenched in education, procurement and contracting. But it is the quiet internationalisation of reform. For decades, domestic politics could not dismantle these preferences. A trade treaty has begun to do so, clause by clause, without a political uprising and without the language of reform.The Long March Ahead

So was the agreement good? For the United States the answer is clear, for it secured both economic gains and lasting strategic leverage. For Malaysia the answer is narrower, because the agreement was good only in the limited sense that it preserved survival, while strategically it imposed costs that will bind us for years to come.

The deeper test will emerge when Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam finalise their own arrangements. If they are compelled to sign agreements that replicate Malaysia’s clauses, then we will be seen as a first mover who secured stability early. If they manage to escape with softer terms, however, Malaysia will stand exposed as the outlier that conceded more than was necessary and did so too quickly.

In the end, Malaysia signed to protect its factories, but the United States signed to project its power. That asymmetry will not be measured in months, but in decades. It is not a question of who won the negotiation. It is a question of what kind of Malaysia will emerge from its consequences.

This is not cooperation. This is delegation. Article 5.1 binds Malaysia to adopt American measures against third countries in the name of U.S. economic or national security. Even among allies, such an obligation is unprecedented. It does not describe partnership. It describes subservience written into treaty text. -

What PETRONAS risked, Moët gained

The global stage: the 2025 Formula 1 Singapore Grand Prix podium, choreographed to the second. Every brand, every gesture, every second of screen-time carries weight.The recent Singapore Grand Prix should have been remembered for the victory of Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS on the top step of the podium, with George Russell taking the chequered flag. It should also have been remembered as the moment McLaren secured the Constructors’ Championship. Instead, it has become remembered for a different image: the President and Group CEO of PETRONAS, magnum of Moët & Chandon in hand, caught on international broadcast spraying champagne as if he were a winning driver.

The incident has since drawn criticism and an apology, which was necessary. Yet the larger question remains. What was gained, and what was lost, when PETRONAS’ brand was projected, for two long minutes, through the imagery of champagne spray.

Formula 1 is not simply a sport. It is a global media product, choreographed to the second, in which every logo, every backdrop, and every gesture is designed to create value. When the PETRONAS CEO took centre stage with a magnum of Moët & Chandon, what PETRONAS risked, Moët gained. One brand saw its equity tied to the dignity of a national oil company; the other secured global exposure in precisely the celebratory context it has long paid handsomely to own.

What PETRONAS risked, Moët gained. A national oil company’s dignity tied, in an instant, to a champagne label immemorialised by Getty Images.The issue is not morality, whether real or performative. It is optics, the question of how corporate leadership embodies the stature of the institution it represents. Picture this: Amin Nasser of Aramco, Darren Woods of ExxonMobil, Mike Wirth of Chevron, Wael Sawan of Shell, Patrick Pouyanné of TotalEnergies, Murray Auchincloss of BP, Magda Chambriard of Petrobras, Anders Opedal of Equinor, Claudio Descalzi of Eni. Can we imagine any of these global CEOs climbing an F1 podium, Moët magnum in hand, to spray champagne.

Leadership is not exercised only in boardrooms, strategy papers or multi-year investments. It is also measured in the split-second moments that matter disproportionately, when instinct collides with the weight of representation. On a stage as visible as Formula 1, the margin for error is almost non-existent. In those seconds, what is done or not done can reshape perception far beyond the moment itself.

PETRONAS has long aspired to stand among the majors. That stature is not measured by sponsorships or trophies alone, but by the restraint and gravitas of its leadership. Optics matter, because in the eyes of global investors, peers, and partners, they signal whether a company is led with the dignity befitting its scale.

Formula 1 delivers the rarest of stages, where every second has global reach. On that stage, the measure of ambition is not whether we are seen, but how we are seen.

Moments of exuberance, but also moments of representation. Leadership is tested not only in boardrooms, but in the split-second images that travel worldwide.Malaysia deserves assurance that PETRONAS will continue to embody the decorum and dignity worthy of its hallowed name. For PETRONAS does not stand only as a sponsor of motorsport, but as the custodian of a national symbol and a global player whose reputation must command respect in every arena.

For what PETRONAS risked in Singapore, Moët gained, and that exchange, above all, must never be repeated.

📌 Footnotes

1. Singapore Airlines Singapore F1 Grand Prix 2025: The race was won by George Russell driving for Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS Formula One Team, with McLaren securing the Constructors’ Championship in the same weekend.

2. Podium protocol: Traditionally, the podium is reserved for the top three drivers and occasionally the representative of the winning Constructors’ team. On this occasion, Tengku Muhammad Taufik represented PETRONAS and Mercedes on the podium.

3. Moët & Chandon: Official champagne supplier to Formula 1 since 1966 (with brief interruptions). Every podium ceremony is choreographed to include its brand exposure.

4. Global oil majors: CEOs referenced – Aramco, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies, BP, Petrobras, Equinor, Eni – are the benchmark comparators for PETRONAS’ aspiration to global stature.

5. Getty Images circulation: The photo of Tengku Taufik spraying champagne has been syndicated by Getty Images, ensuring enduring visibility beyond the initial broadcast.

Editor’s Note: The footnotes are provided solely to situate the commentary in factual context. This essay does not question personal integrity, but reflects on institutional optics and the symbolism of leadership on a global stage. The images referenced are part of the public domain of Formula 1’s official broadcast and syndicated media.

-

The Ultimate Fall Guy

Washington politics, the 1MDB scandal, and the man who carried its weight

Every political system requires fall guys. They are the figures who absorb the punishment so that institutions may endure and leaders may survive. In Washington the fall guy is a familiar instrument of power, providing the spectacle of accountability without the cost of dismantling the system itself. The 1MDB affair, often narrated as a Malaysian scandal, was equally a Washington story. It intersected with three American presidencies, each consumed by its own partisan battles, and in each phase someone had to take the fall. The cast changed over time, ranging from financiers and lobbyists to celebrities and even an entire nation, but the narrative logic was constant. At the centre of it all stands Najib Razak, the one man who unlike the intermediaries and enablers scattered across the globe remains imprisoned, contested, and indelibly branded. He is the ultimate fall guy, the enduring symbol of a scandal far larger than himself.

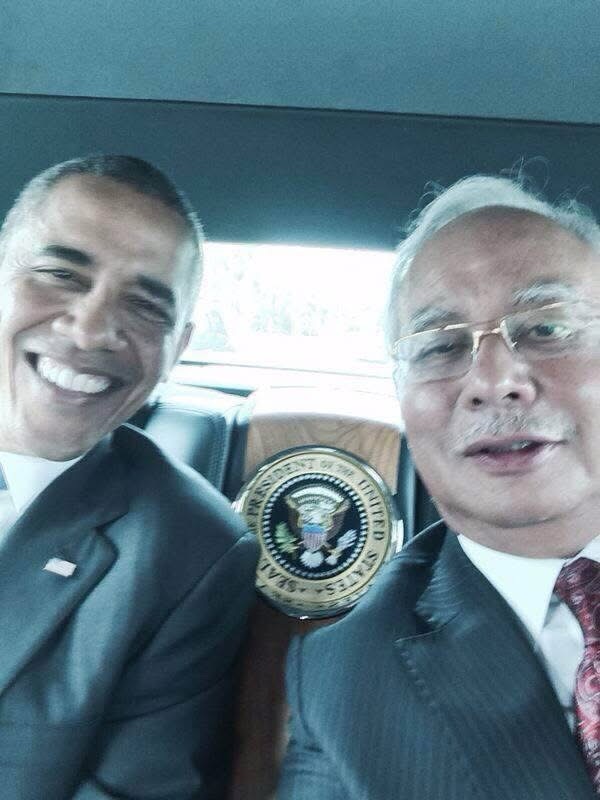

The scandal first arrived on the world stage in Washington in July 2016 when then Attorney General Loretta Lynch and senior Justice Department officials announced what they described as the largest kleptocracy case in history. The phrase was deliberate. It was theatre as much as law. For the Obama administration, besieged by questions of credibility after the Panama Papers and eager to claim leadership in the fight against global corruption, 1MDB was the perfect case. It had all the optics: billions siphoned from a sovereign fund, yachts and Beverly Hills mansions, Hollywood films and Leonardo DiCaprio, diamonds and Picassos. It was corruption already written for a movie script. And critically, Malaysia was a safe target. Large enough to dramatise, small enough to be expendable. Unlike Russia or China, it would not retaliate. Unlike Gulf sovereign funds, it was not a vital American ally. So Malaysia, and Najib Razak as its prime minister, became the showcase villains.

Meanwhile, the global enablers of 1MDB’s flows, the banks that moved the money, the Hollywood auction houses and galleries that sold the art, and the Gulf intermediaries who cut deals with the proceeds, all escaped the full glare. The Department of Justice got its global theatre, Malaysia bore the shame, and the world learned the name 1MDB. From the very beginning the narrative had already chosen its fall guy.

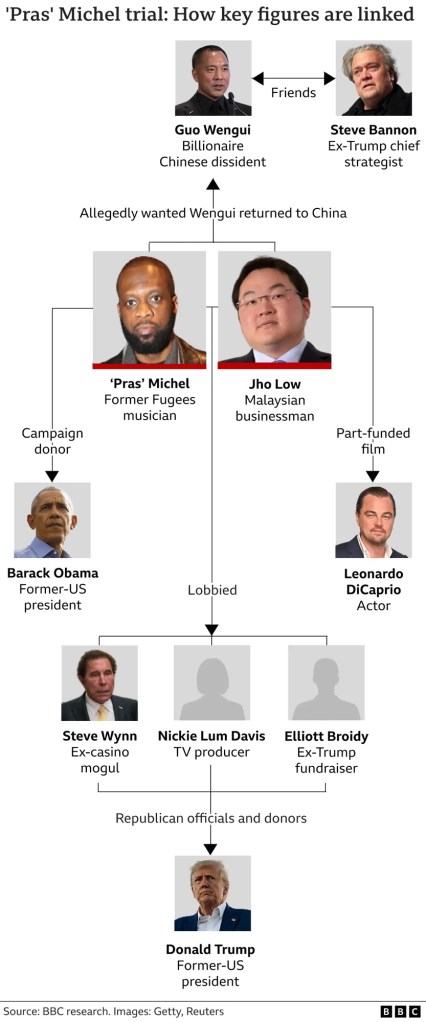

Under Trump the story did not fade. It re-entered Washington through its most porous channel, which was money. By 2017 Jho Low was desperate. His yacht had been seized, his assets frozen, and indictments loomed. So he did what the wealthy have always done in Washington, he hired lobbyists. The celebrity conduit was Pras Michel, the Fugees rapper. The political operator was Elliott Broidy, a Republican fundraiser and deputy finance chair of the RNC. The goals were audacious. Persuade the Department of Justice to abandon the 1MDB prosecutions and engineer the extradition of Chinese dissident Guo Wengui as a favour to Beijing. In return Broidy was promised tens of millions.

But the timing was fatal. Washington was already aflame with the Mueller investigation and accusations of Russian influence. The Justice Department, accused of bias from all sides, needed credibility. And credibility meant proving that foreign lobbying would not be tolerated even when Republicans were involved. So Broidy became expendable. Indicted in 2020, pleading guilty to conspiring to violate the Foreign Agents Registration Act, he was abandoned by his party and pardoned only on Trump’s last day. Pras Michel followed the same arc. Indicted in 2019 and convicted in 2023, he became the celebrity face of foreign influence gone wrong. Both were fall guys, useful to prosecutors, satisfying to the press, and ultimately forgettable.

Meanwhile, the real architecture of the scandal, the banks that moved the money, the industries that absorbed it, the sovereign allies who profited from it, remained untouched.

The transition from Trump to Biden changed the players but not the script. Biden’s Justice Department continued to prosecute intermediaries. Pras Michel’s trial reached its conclusion, Tom Barrack was indicted for lobbying on behalf of the UAE, and others were caught in the long tail of FARA enforcement. These cases served the same function as before. They were high-profile, safe, and foreign enough to dramatise institutional vigilance without destabilising the core system. They showed continuity, not reform. The deeper pipelines of money and influence, Wall Street, K Street, Gulf capitals, stayed intact. Fall guys remained indispensable to Washington’s narrative of accountability.

Across three presidencies the roll call of fall guys grew. Broidy, Michel, Barrack, and others passed across the stage. But none bore the weight that Najib Razak has borne. For the Department of Justice he was the name that validated the largest kleptocracy case in history. For Malaysia’s opposition he was the villain whose downfall enabled their improbable electoral victory in 2018. For global media he was the shorthand that made the story travel, a prime minister entangled in a billion-dollar heist. And unlike Jho Low who vanished into exile, Najib stayed. He faced trial, conviction, and imprisonment. He received a partial pardon, yet remains in prison. He continues to be contested in Malaysian politics, his fate still debated, his name permanently linked to the scandal. Najib became and remains the ultimate fall guy, not only for Malaysia’s transformation but for Washington’s partisan theatre and for a global financial system too fragile to put itself on trial.

The story of 1MDB is therefore not just about money, it is about narrative. Who controls it, who amplifies it, and who is drowned out by it. Under Obama Malaysia was the convenient fall guy for global anti-corruption theatre. Under Trump intermediaries like Broidy and Michel were sacrificed to sustain the credibility of the Department of Justice amid partisan fire. Under Biden the pattern endured, prosecutions continued, and the system could still claim vigilance. But through it all Najib Razak became everyone’s fall guy, the man whose downfall served Washington’s credibility, Malaysia’s political change, and the world’s appetite for a morality tale. That does not erase his own role in 1MDB, nor does it absolve him of having gained from what unfolded under his watch. What it does show is how a scandal that implicated financiers, bankers, lawyers, celebrities and governments across continents ultimately resolved itself into the fate of a single man.

Narratives matter more than facts. They decide who is punished, who is protected, and who is remembered. And in the case of 1MDB Najib Razak was not the architect, but he became the beneficiary most exposed, and in the end, the narrative that endured.

-

When the Storyteller Becomes the Story

“You tell the world where he is. You show the passport. You name the mansion. And yet, not one demand from Washington to bring him to justice.”

That was the question I posed not in anger, nor in defence, but as a call for moral consistency. It was neither partisan in origin nor rhetorical in tone. It asked only this: if one claims to expose injustice, must one not confront it in every direction?

The responses that followed did not disappoint. They also revealed more than I had expected.

⸻

I. The Double Standard That Holds

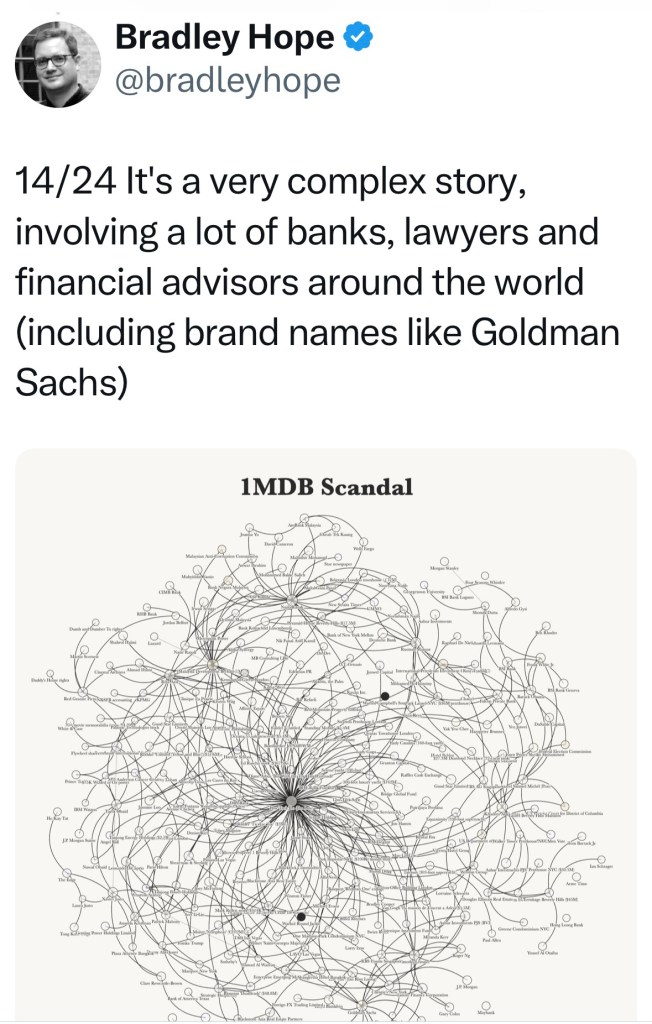

Bradley Hope and Tom Wright were once praised for their early work uncovering the mechanics of the 1MDB scandal. Their reporting helped internationalise the narrative and frame Jho Low in the global imagination. The impact of their book Billion Dollar Whale was real and for that, they earned respect – and global attention.

But something fundamental has shifted in the years since. No longer reporters bound by institutional rigour, they now operate as brand custodians of a global content platform. Their posture remains investigative, but the substance has shifted. They have ceased to investigate power in all its forms and have begun to curate narratives in a way that is editorially convenient and commercially useful.

When they published a thread identifying what they claimed to be Jho Low’s false passport and mapped his villa in Shanghai, the implications were serious. The man at the centre of the world’s most audacious financial scandal is no longer hiding. He is living in plain sight. His location is not speculative. It is known. By them. By the Department of Justice. And most likely, by many others with the power to act.

Tom Wright’s exposé of Jho Low’s alleged Shanghai location, complete with photo of a false passport and villa overhead.But they did not direct their questions at Washington. They did not ask why no diplomatic action had been taken. They did not ask why the same country that located Osama bin Laden and retrieved him from a fortified compound halfway around the world appears unable (or unwilling) to bring Jho Low to justice.

Instead, they turned their attention once more to Malaysia.

⸻

II. A Deflection Disguised as Precision

I engaged. Politely. Transparently. I asked whether any pressure had been applied by those in Washington who have jurisdiction over Jho Low, who indicted him under U.S. law, who recovered billions in stolen assets, and who benefitted from the extradition of a Malaysian citizen to stand trial in their courts.

Tom Wright replied, “He’s Malaysian.”

As if that settled the matter. As if that absolved the United States of responsibility. As if jurisdiction were a matter of birthplace, rather than binding law.

Wright’s reply to my public query on U.S. inaction: “He’s Malaysian.”

A three-word shrug.Before I published this post, I had asked a quieter question in a different context, prompted not by provocation but by something I could not ignore. Bradley Hope had shared a visually intricate map of the 1MDB scandal, intended to show the complex web of individuals and institutions involved. But two nodes were blacked out. They were not banks or jurisdictions. They were names. And they were names that, from what could be discerned, pointed not to Malaysian actors, but to figures associated with the Trump campaign.

I noted this publicly, not to accuse, but to observe. Hope responded with civility and restraint. Tom Wright, by contrast, dismissed the comment altogether. “This guy accusing us of something? Hard to understand.”

That reaction was instructive. The discomfort did not lie in what was said, but in what had been seen. The redactions were not accidental. They were deliberate choices. And those choices revealed that the story, at least in part, was no longer being told in full.

At that moment, it became clear to me that we were no longer dealing with journalism in its purest form. We were witnessing its transformation into something else: selective narrative, editorial control, and ultimately, performance.

Bradley Hope’s own visual reconstruction of the 1MDB scandal. Amid the many connections mapped, two names are redacted—despite the public domain record of their involvement. The omissions are not editorial oversights. They are deliberate narrative choices.Roger Ng is also Malaysian. He was arrested, flown over ten thousand miles, and tried in Brooklyn. He was handed a ten-year sentence by a U.S. federal judge. His citizenship did not shield him. Nor should it have.

Malaysia prosecuted its former Prime Minister who was found guilty and is now imprisoned. Malaysia cooperated fully with the DOJ. Malaysia bore the political cost of reform and accountability. Malaysia has never denied its institutional failings.

But it is not Malaysia that knows where Jho Low is today. It is not Malaysia that holds the legal indictment under its own statutes. It is not Malaysia that possesses the geopolitical tools to act, and yet has chosen not to.

⸻

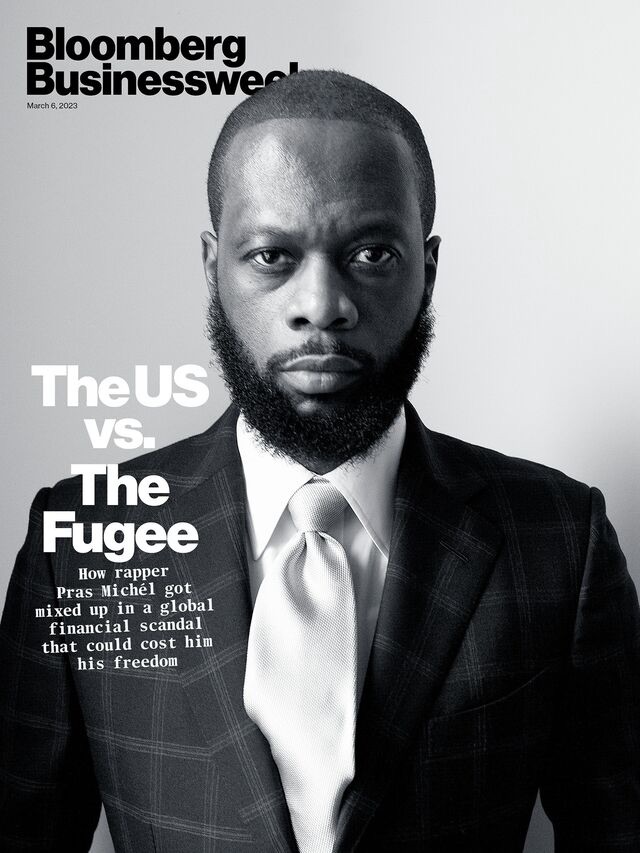

III. The Descent from Journalism to Franchise

And then came the real reveal.

On the same thread that identified Jho Low’s alleged location, just beneath the investigative claims, appeared a link.

“Jho Low World Tour. 2009–2025.” Printed on a black T-shirt. Available for purchase. Promoted on the same account. Branded under the same media studio.

This is not journalism.

A novelty T-shirt marketed by Brazen.fm bearing Jho Low’s image and the label “World Tour 2009–2025.” Promoted on the same platform used to expose his whereabouts, the product blurs the line between justice and merchandising.This is merchandise created in the likeness of a man they claim to hold responsible for the worst act of financial pillage in Malaysia’s history. It is difficult to reconcile that moral posture with the decision to commercialise it on a novelty shirt.

No serious journalist at The Wall Street Journal, where both men once worked, would imagine monetising their reporting in this way. No Pulitzer-winning newsroom would permit it. And no editor of integrity would defend it.

And yet, here we are.

When those who once chronicled justice begin to sell the image of the fugitive they helped immortalise, it no longer matters what they say about others. Their actions have become the story.

⸻

IV. What This Is Actually About

Let me be clear. This is not a defence of Najib Razak. It is not a partisan diversion. It is not a plea for absolution.

I testified under oath. I submitted myself to legal scrutiny. I do not need to re-litigate that here.

But I will not remain silent when others who once stood for accountability begin to insulate themselves from it. If you invoke the language of justice, then you must be prepared to answer to its demands. If you trade on the authority of journalism, then you must accept the responsibilities that come with it. You cannot hold others to account while evading scrutiny yourself.

Nor can you condemn a small nation’s failings while averting your gaze from the silence of superpowers.

Malaysia has many flaws. We have paid a price. We continue to pay it. But we have never protected Jho Low.

The country that knows where he is and chooses not to act is not Malaysia.

⸻

V. Final Observations

This is no longer a story about a fugitive alone. It is a story about those who now curate his narrative, profit from his notoriety, and offer judgment from a safe and selective distance.

It is also a story about what journalism becomes when it crosses the line into performance. When truth is no longer pursued for its own sake, but tailored for spectacle and tailored to sell. When T-shirts replace testimony.

If Tom Wright and Bradley Hope wish to become public commentators, then they must accept public scrutiny. If they choose to market their reporting as a product, they must also accept the consequences of commodifying justice.

I would not have written this if they were mere provocateurs. But they speak from the prestige of institutions they once served with distinction. They should carry that weight with honour.

Because if they will not bear that responsibility, others must.

Postscript:

Once, they chased the story.

Now, they sell the narrative.

From watchdogs to showrunners, the transformation is complete. -

The Pied Piper Of Putrajaya

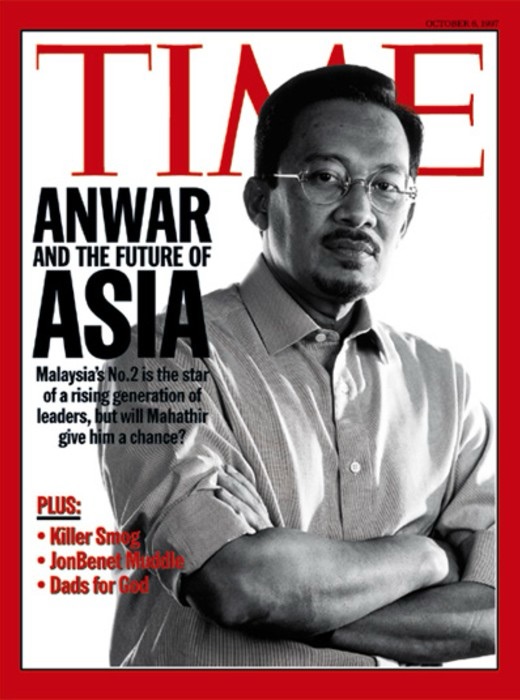

Time Magazine cover, October 6, 1997: Anwar Ibrahim, then Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister, featured with the headline “Anwar and the Future of Asia.”Malaysia today faces an unusual contradiction.

On the surface, we are told the economy is recovering. Investment is flowing. Subsidies are being rationalised. The GST debate is over. A medium-term revenue strategy is in motion. And inflation, we are assured, remains contained.

But underneath this well-rehearsed narrative, a deeper anxiety simmers. Business leaders are cautious. Civil servants are frustrated. Investors are confused. The rakyat, particularly the urban middle and lower-income households, feel poorer despite all official assurances to the contrary.

And at the heart of that disconnect lies a fundamental question:

Who exactly is responsible for the economy, and where are they taking it?

Global Headwinds but Local Agency Matters More

Yes, global conditions are tough.

Geopolitical fragmentation, prolonged high interest rates, supply chain realignments, and new waves of industrial policy from Washington to Brussels have all reshaped the global trade order. Malaysia is not immune. Nor is any small, open economy.

But let us not pretend that our current economic condition is purely the result of global tides.

Growth is now consistently trailing pre-pandemic trends. Real wages have barely moved. Household debt remains among the highest in Asia. Our fiscal position is tightening not because of a sudden crisis, but due to long-standing policy deferrals and structural complacency.

This is not external fate. This is internal design.

The Data Does Not Lie, But It Does Accuse

Based on official data released by Bank Negara Malaysia and the Department of Statistics, Malaysia’s federal government debt at end-2024 stood at RM 1.1725 trillion. The country’s GDP for the same year was RM 1.6503 trillion.

This puts our debt-to-GDP ratio at 71.05 percent, well above the statutory ceiling of 65 percent as mandated by the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2023.

This is not a speculative concern. It is a factual, legal breach.

Section 4 of the Act sets the ceiling. Section 10 mandates disclosure to Parliament and submission of a fiscal recovery plan if breached. Neither has taken place.

Beyond debt figures, other structural signals are flashing amber. Real wage growth remains tepid. Median household income has stagnated. Budget deficits have exceeded 5 percent of GDP for several consecutive years. FDI inflows remain uneven. Malaysia’s export competitiveness is under renewed threat as global supply chains recalibrate and tariffs loom on the horizon.

These are not isolated metrics. They represent a structural erosion of economic resilience.

A Government of Two Minds

Within this administration, there is a growing tension between two conflicting economic impulses.

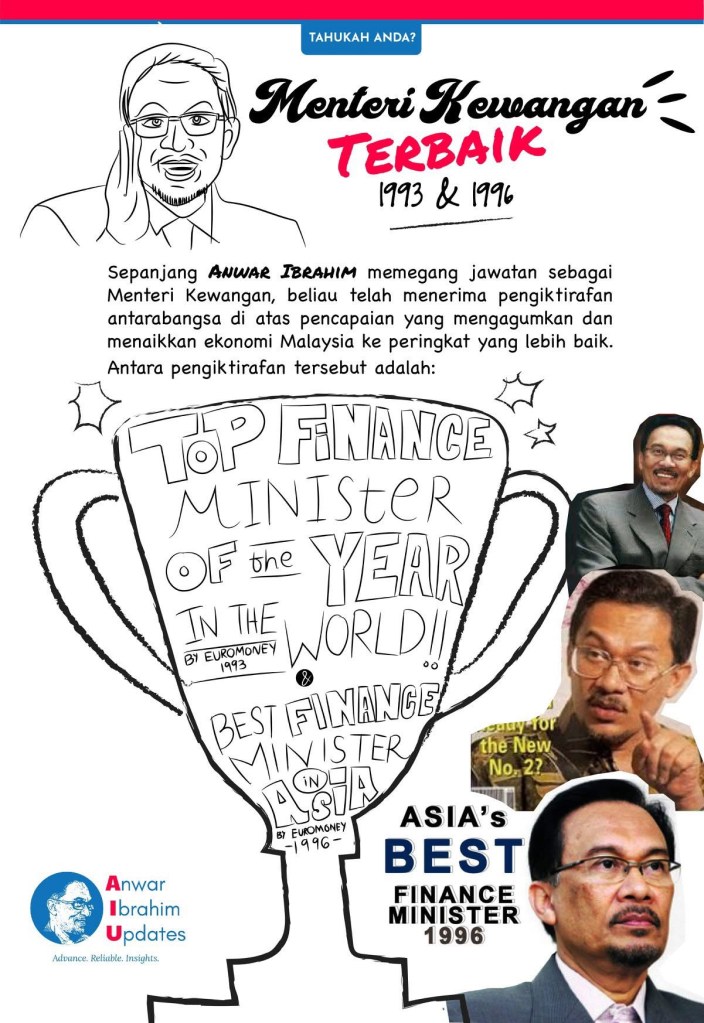

Infographic celebrating Anwar Ibrahim’s tenure as Malaysia’s Finance Minister, highlighting accolades received in 1993 and 1996 including “Top Finance Minister of the Year” by Euromoney and “Asia’s Best Finance Minister” by Asiamoney.The first is rooted in Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s legacy as a 1990s reformer. It privileges fiscal discipline, macroeconomic credibility, and technocratic rule-based governance. This impulse recalls the Anwar who, during the Asian Financial Crisis, embraced a form of fiscal restraint that mirrored IMF conditionality, albeit without IMF involvement.

The second impulse is populist and reactive. It prioritises visible relief measures over long-term structural shifts. It maintains fuel subsidies, expands social spending, and introduces selective tax exemptions with minimal targeting. These measures are often politically expedient but economically incoherent.

The result is a confused hybrid. Diesel subsidies are cut, but apples and oranges are exempted from tax. SST is expanded to professional services, yet revenue measures are not accompanied by a broader tax reform agenda.

What emerges is neither technocratic clarity nor populist certainty. Instead, we see the contours of drift.

At some point, governments must match institutional authority with political accountability.

This is not a legacy crisis inherited from past administrations. The Fiscal Responsibility Act was tabled, debated, and passed by the current government. The appointments to key ministries were made by the current Prime Minister. The budget, subsidies, and fiscal projections were approved under his direct authority.

Power has been centralised. So must responsibility.

A government cannot consolidate executive control and then plead operational constraints when results fall short.

The PKR State: Who Holds the Commanding Heights

Using the British concept of the commanding heights, a term that refers to strategic sectors that shape national economic direction, the picture in Malaysia is unambiguous.

Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) now holds or controls the three most powerful economic levers in government.

First, the Ministry of Finance, held by the Prime Minister himself.

Second, the Ministry of Economy, entrusted to a technocrat personally appointed by the Prime Minister.

Third, the Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry, led by a trusted PKR affiliate and Anwar ally.

These three ministries determine where capital flows, which industries rise, who gets taxed and who gets exempted, how government-linked companies are governed, and where Malaysia positions itself within the global economy.

This is not just policy centralised. This is power held tightly.

More Than Ministries: Who Controls the Crown Jewels

In addition to these economic super-ministries, three of the country’s most powerful economic institutions are also directly answerable to Anwar.

PETRONAS, the national oil company and single largest contributor to government revenue.

Khazanah Nasional, the country’s sovereign wealth fund.

Permodalan Nasional Berhad, the institutional guardian of Bumiputera capital ownership.

Together, these six nodes comprising three ministries and three national institutions define the architecture of Malaysia’s modern economy. Never before has so much institutional power over money, capital, and economic direction been concentrated under the personalised authority of a single Prime Minister.

And so the question must be asked, not as a political jab but as a matter of governance and strategic capacity:

Can one man, even a long in the tooth veteran like Anwar, truly manage it all – even via his chosen surrogates?

The Debt Breach: A Crisis of Credibility

Let us now turn to the fiscal fundamentals.

As outlined earlier, Malaysia’s federal debt has breached the statutory ceiling by over 6 percentage points. This is not an academic violation. It is a statutory breach of a law passed just 18 months ago by this very government.

Section 10 of the Act requires the Finance Minister to notify Parliament and present a recovery plan. As of now, no such report has been filed. No such plan has been disclosed. No such transparency has been attempted.

The Risk of Institutional Paralysis

We now face a dangerous institutional moment.

The government writes a law. The government breaks that law. The government delays admitting it. And the institutions around it, including the civil service, Parliament, and financial regulators, go silent.

This is not a crisis of fiscal numbers. It is a crisis of fiscal accountability.

If laws passed by Parliament are quietly breached and then retroactively justified, the entire framework of public governance is weakened.

Malaysia deserves better than compliance theatre. Parliament reconvenes in a week. Who will hold Putrajaya to account?

All Roads Lead to Anwar but Where Is He

This brings us to the most difficult but essential point.

If Anwar Ibrahim holds the Finance portfolio, leads the political party that dominates the economic ministries, and appoints the heads of PETRONAS, Khazanah, and PNB, then the economic buck stops with him.

And yet, he is nowhere near the helm.

His attention is increasingly diverted by a string of foreign trips and summits, personal judicial entanglements including a landmark immunity hearing scheduled for 21 July, and endless rounds of party-political signalling, while PKR itself struggles to define its governing identity.

He has time for media interviews and crowd rallies, but not for a formal statement to Parliament on a breach of fiscal law.

He has time to exempt fruit from SST, but not to account for why fiscal discipline collapsed under his watch.

Conclusion: The Leadership Void

Malaysia does not lack economic talent.

Malaysia does not lack institutions.

Malaysia does not even lack plans.

What it lacks is clear economic leadership.

Until that changes, until the Prime Minister chooses to lead the economy rather than outsource it, distract from it, or delay difficult choices, the risk is not simply fiscal. It is systemic.

And if he will not lead it, someone else eventually will.

But not before things get much worse.

Footnote:

For those less familiar with fiscal policy, here is why the debt to GDP breach matters — and why it is not just academic:

📉 1. Borrowing headroom is now constrained

With civil service salaries and pensions absorbing most of the operating budget, any fiscal squeeze lands hardest on development spending. This means roads, railways, schools and digital infrastructure are often the first to be delayed or cancelled. These are the projects that stall.

⏳ 2. Delays in payments to suppliers

When liquidity tightens, ministries begin to defer payments — whether for IT systems, medical equipment or engineering works. Multi month arrears to private sector vendors disrupt cash flow and echo through the entire supply chain.

📆 3. Greater use of deferred procurement structures

To avoid recording large debts upfront, the government turns to alternative arrangements such as build lease transfer (BLT) and public private partnerships (PPP) schemes. These stretch payments over 10 to 30 years, deferring the financial burden but constraining future budgets.

💸 4. Higher taxes and stricter enforcement are likely

To close the gap, the government will turn to revenue measures. Expect broader service tax coverage or new taxes such as carbon pricing or capital gains. The reintroduction of the GST is no longer unthinkable. Enforcement will also tighten — with more audits and more aggressive collections by the tax authorities and Customs.

🔍 5. More tax audits and penalties, even for GLCs.

The revenue crunch has already triggered back assessments across corporate Malaysia. Tenaga Nasional and PETRONAS were among the first. No company is immune. Enforcement is now part of fiscal strategy.

📊 Bottom line

A breach of the Fiscal Responsibility Act is not a legal footnote. It is a structural constraint that reshapes policy, reallocates risk, and sends signals far beyond the numbers. The real economy will feel the consequences.

-

Turning 100 Should Transcend Politics

Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad turns 100 today.

In most nations, this would be cause for national reflection. Not because of unanimous admiration, but because of historical magnitude. A centenary invites us to pause, to reconcile, and to ask not just what he was, but what we have become.

Instead, we have seen something else: muted institutional response, cautious political triangulation, and silence from state-linked bodies that ought to be record-keepers of national memory, not just instruments of political convenience.

A Life Larger Than Politics

Tun Dr Mahathir served as Malaysia’s Prime Minister not once, but twice. First for 22 years. Then again for 22 months.

He oversaw the rise of our industrial economy, created a dominant Malay capitalist class, opened the door to global markets, and left behind infrastructure – both physical and institutional – that continues to define the country.

He was, and remains, a deeply controversial figure. His legacy invites debate: from the centralisation of power to the weakening of judicial independence, the unresolved wounds of Ops Lalang, and most recently, his combative role post-retirement. But these debates are precisely why he cannot be ignored. He is embedded in our political DNA.

When Churchill Turned 100

When Winston Churchill turned 100 in 1974, Britain did not hesitate.

The BBC aired documentaries, replayed his speeches, and launched public retrospectives. Editorials debated his legacy. Archives were opened, not sealed.

This was not under a Conservative government – Churchill’s own party – but under Prime Minister Harold Wilson, leader of the Labour Party and Churchill’s lifelong political rival.

Wilson’s government had also presided over Churchill’s state funeral in 1965, attended by monarchs and presidents. And yet, in both death and commemoration, Britain understood this:

That marking a centenary is not about agreement.

It is about national memory.

It is about respecting history and rising above the politics of the day.

The Office Must Outlive the Man

Honouring a centenary is not a political endorsement. It is an act of democratic maturity.

It signals that we are capable of separating public memory from partisan allegiance. That we honour the role, not just the man. That we can acknowledge our past leaders even when we disagree with them.

To let Mahathir’s 100th pass with minimal institutional remark is to abdicate our responsibility as stewards of history. It denies young Malaysians the opportunity to understand the arc of national leadership in all its complexity and consequence.

The Cost of Silence

This silence is not neutral. It tells us who we are: still a country where history is written only by the present victor. Still a country where political discomfort overrides institutional memory. Still a country where turning 100 does not insulate a man from the anxieties of the moment.

We cannot allow our public memory to be this fragile.

When a man who helped build the very scaffolding of the modern Malaysian state turns 100, our duty is not to erase his controversies. It is to mark the moment with full clarity: his role, his rise, his rupture, and his relentless imprint.

Final Reflections

You don’t have to agree with Mahathir. I often haven’t. But you cannot erase him.

And a country that fails to mark his centenary with the seriousness it deserves is not punishing the man. It is diminishing its own sense of history.

Turning 100 should have been our breakthrough. A chance to rise above partisan instinct and model something nobler.

That we didn’t says more about us than it does about him.

It is not too late to correct course.

-

Between Mercy and Immunity: The Constitution Cannot Be Selective

Over the past few months, Malaysia has been confronted with two converging constitutional flashpoints:

A Royal Decree for Najib Razak’s house arrest that was issued but ignored by the executive, and an attempt by the Attorney General to shield Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim from a civil sexual harassment suit on the grounds that litigation would impair his ability to govern.

Both issues invoke fundamental provisions of Malaysia’s constitutional architecture. Together, they raise uncomfortable questions about whether constitutional principles—particularly the limits of executive accountability and the exercise of royal prerogative—are being applied consistently, or selectively.

Two Decrees, Two Outcomes

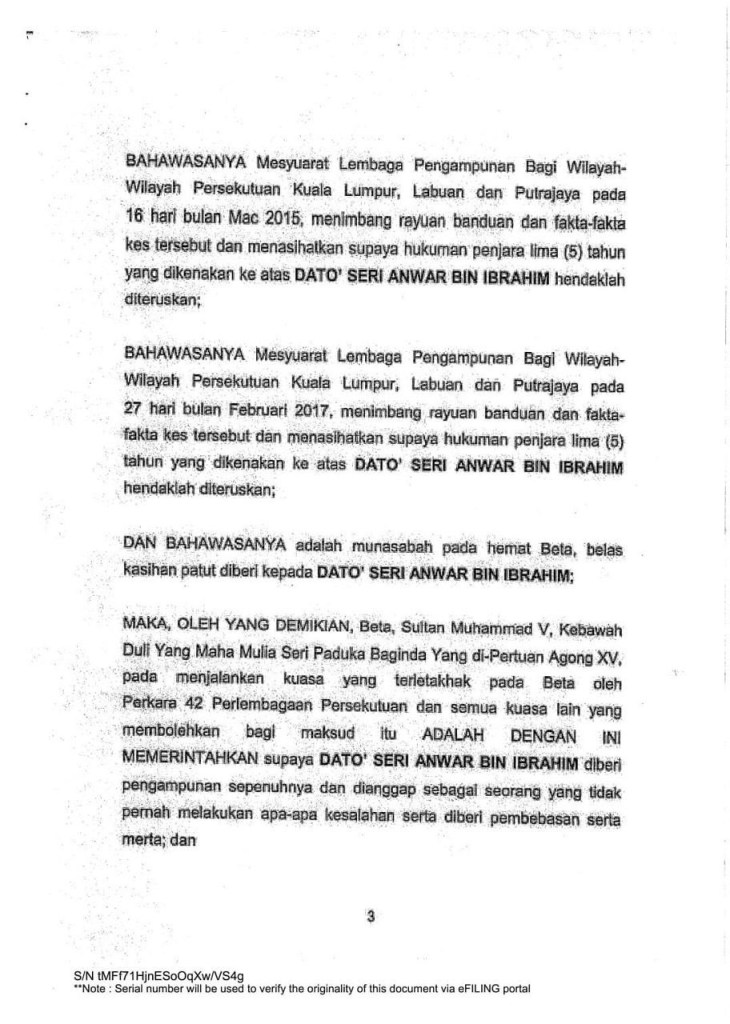

In May 2018, the 15th Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Sultan Muhammad X, issued a full pardon to Anwar Ibrahim following a Pardons Board meeting convened 443 days earlier. The constitutional vehicle was Article 42, which grants the King the power to pardon or commute sentences upon receiving advice from the Pardons Board.

Despite his well-documented personal scepticism, then–Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad signed the Royal Order without delay, giving full effect to the decree. Anwar was released from prison within hours. At the time, this swift execution of the King’s order was widely regarded as a restoration of justice—and a principled act of statesmanship by a Prime Minister who set aside political rivalry to uphold the Constitution.

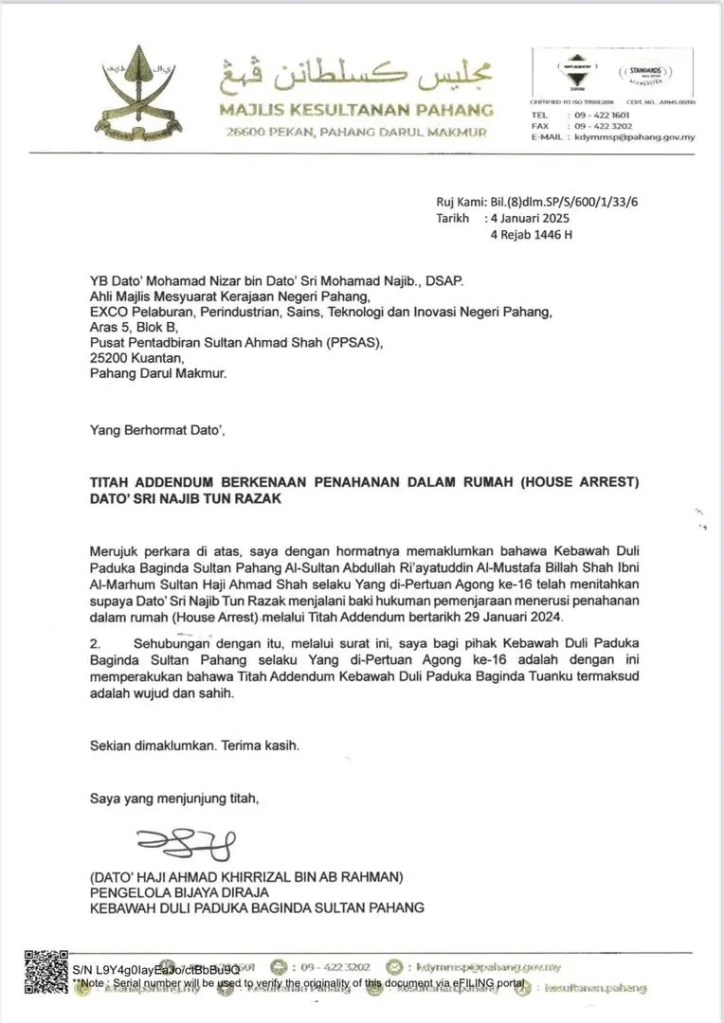

Fast-forward to 2024. The 16th Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Sultan Abdullah, issued a Titah Addendum directing that former Prime Minister Najib Razak serve the remainder of his prison sentence under house arrest—a reprieve, not a full pardon, but one granted under the same provision of Article 42.

As in 2018, this decision came after a validly convened meeting of the Pardons Board. Yet unlike in Anwar’s case, the Titah was met with silence. The Prime Minister’s Office offered no acknowledgment. The Attorney General did not act to implement it. For weeks, the public was told it was mere rumour. It was only after the Pahang Palace issued a formal confirmation that the Addendum’s existence was officially recognised.

This contrasting treatment—same constitutional basis, same royal institution, same executive authority, but opposite responses—demands scrutiny.

The Legal Framework: Article 42

At the heart of both cases lies Article 42 of the Federal Constitution, which governs the Royal Prerogative of Mercy. The provision reads, in part:

“The Yang di-Pertuan Agong has power to grant pardons, reprieves and respites… upon the advice of the Pardons Board.”

That phrase—“upon the advice”—has long been interpreted by courts and constitutional scholars to mean that the King must be advised, but is not bound by the Board’s recommendation. It is not merely a procedural consultation; the discretion ultimately remains with the monarch.

In 2018, this principle was respected. Sultan Muhammad X rejected the 2017 Board’s recommendation to uphold Anwar’s sentence and instead exercised his discretion to pardon. Mahathir, despite personal hesitation, acted in accordance with the decree.

In 2024, Sultan Abdullah chose to exercise similar discretion in Najib’s case—granting a reprieve, not a pardon. But this time, the Prime Minister did not act. No explanation was offered. The Attorney General did not even disclose the existence of the Addendum to the court in subsequent proceedings, leading to a contempt motion being filed against him.

Political Selectivity in Execution

In a widely shared X thread, I asked a direct question:

If your political nemesis could set aside his reservations and implement the King’s order for you in 2018, why could you not do the same for Najib in 2024?

This is not a moral comparison between individuals. It is a constitutional comparison between outcomes.

Both the Anwar and Najib decrees were:

Issued under Article 42, made following a Pardons Board meeting, signed by a reigning YDP Agong, delivered to a sitting Prime Minister for implementation.

Yet only one was acted upon. The other was ignored, and actively withheld from judicial proceedings—despite its clear constitutional standing.

Immunity and the Double Bind

This pattern is made more troubling by a recent move by the Attorney General to apply for a Federal Court ruling on whether Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim should be entitled to immunity from civil litigation while in office.

The claim is that defending a sexual harassment suit—filed by Anwar’s former speechwriter—would impair the Prime Minister’s ability to perform his duties.

The optics are now deeply problematic:

A Royal Decree benefitting someone else is ignored. A civil suit implicating the Prime Minister is deferred. Constitutional discretion is withheld from political rivals but claimed for personal protection.

This is not merely legally inconsistent. It is corrosive to public trust in constitutional governance.

Rule of Law or Rule of Preference?

The rule of law depends on consistency—across time, across cases, and across personalities. When identical constitutional instruments are treated differently depending on who they favour, the appearance is one of selective enforcement. That is damaging not just to the reputation of the executive, but to the institutional credibility of the Attorney General’s Chambers, the Cabinet, and the wider government.

Malaysia cannot afford a system where:

Clemency is implemented for one leader but denied for another, Royal orders are honoured when politically expedient and disregarded when they are not, a sitting Prime Minister is shielded from civil accountability while others are denied relief from incarceration already approved by the monarch.

A Final Note

Malaysia’s constitutional monarchy is not ornamental. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong, acting within his constitutional powers, represents a stabilising force between institutions. Article 42 is not a ceremonial device; it is a substantive legal mechanism that, when used, must be respected—no matter who benefits.

If one Royal Decree can be ignored, and one civil suit evaded, what remains of the rule of law?

The true test of a constitutional democracy is not how power is used when it suits us—but how power is respected when it does not.

Postscript:

On 3 June 2025, the Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) issued a public statement in response to Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s assertion that the Royal Pardon granted to Anwar Ibrahim in May 2018 was unconstitutional. The AGC sought to correct the record, asserting that a properly constituted Pardons Board meeting did take place on 16 May 2018, and that the Prime Minister at the time, Dr Mahathir, was in attendance.

However, while the statement may appear to settle the issue at face value, a closer examination reveals several critical ambiguities with constitutional and procedural implications—particularly relating to quorum, composition, and the role of the Attorney General.

1. AGC Affirms the Existence of a Pardons Board Meeting

The AGC’s statement confirms that a Federal Territories Pardons Board meeting was convened at Istana Negara at 11:00 AM on 16 May 2018, chaired by His Majesty Sultan Muhammad V, then the 15th Yang di-Pertuan Agong. It asserts:

“Mesyuarat Lembaga Pengampunan tersebut telah dipengerusikan oleh Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong XV Sultan Muhammad V dan turut dihadiri antaranya oleh YAB Tun Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad sendiri selaku Perdana Menteri pada masa itu.”

This line, while affirming Mahathir’s presence, stops short of confirming the attendance of any other members, nor does it specify in what official capacity he attended—an issue that has legal ramifications.

2. Article 42(10) and the Requirement of Quorum

Under Article 42(10) of the Federal Constitution, a Pardons Board meeting must include at least three members, not including the Yang di-Pertuan Agong:

“The presence of three members shall be necessary to constitute a quorum.”

The members required under Article 42(4)(aa) are:

The Attorney General (ex officio), The Minister responsible for the Federal Territories, and Up to three members appointed by the YDPA.

The AGC’s statement does not disclose whether any of the appointed members or the Attorney General were present in person. The lack of such information raises legitimate doubts about whether constitutional quorum was satisfied.

3. Ambiguity Surrounding the Attorney General’s Attendance

The AGC further states:

“Bagi tujuan mesyuarat tersebut, Peguam Negara juga telah memberikan pendapat bertulis mengenai perkara itu selaras dengan Fasal (9), Perkara 42 Perlembagaan Persekutuan untuk pertimbangan Lembaga Pengampunan.”

This suggests that the Attorney General may not have attended the meeting physically, instead submitting a written opinion as permitted under Article 42(9).

While written advice satisfies the AG’s advisory duty, it does not count towards quorum unless the AG was physically present as a Board member. This distinction is crucial: an advisory function does not substitute for membership presence for the purpose of quorum.

4. Was Dr Mahathir Acting as the FT Minister?

Another unresolved question is whether Dr Mahathir held the portfolio of Minister for the Federal Territories at the time of the meeting.

He was sworn in as Prime Minister on 10 May 2018, but no other ministers were appointed or gazetted until 21 May 2018. Therefore, on 16 May, he was the only formally appointed member of the executive.

If Mahathir was not officially gazetted as holding the FT Ministry, his presence may not have satisfied the constitutional requirement under Article 42(4)(aa). The AGC statement does not clarify whether he held or acted in that role.

5. Legal Consequences of the Uncertainty

The constitutional legality of the 2018 pardon hinges on whether:

At least three Board members (excluding the YDPA) were physically present; The AG’s written advice alone sufficed, or whether physical presence was necessary; Mahathir’s attendance was in a qualifying constitutional capacity; Any appointed members of the Board were present at all.

If the quorum was not met, a potential argument arises that the YDPA relied on the advice from the earlier Pardons Board meeting of 27 February 2017, where Anwar’s application was previously considered. In such a case, the 2018 meeting would be treated not as a deliberative meeting, but as a ceremonial or administrative moment to formalise the YDPA’s change of heart—a discretionary act clearly within the monarch’s powers under Article 42(1).

However, the AGC’s refusal to clarify the full attendance list weakens the robustness of its constitutional defence and leaves the legal narrative inconclusive.

6. Broader Institutional and Political Ramifications

While this controversy may appear historic, it has immediate relevance to current debates—particularly surrounding the 2024 Titah Addendum involving Najib Razak. Critics will now argue that:

Both pardons involved discretion exercised by the YDPA, following Board advice; The Anwar pardon was implemented immediately, despite procedural doubts; The Najib clemency decree has been left unimplemented, allegedly on the basis of procedural ambiguity.

This creates a perception of inconsistent treatment of royal clemency decisions depending on political alignment.

Until these ambiguities are resolved, the procedural regularity—though not necessarily the legal validity—of Anwar Ibrahim’s 2018 pardon remains open to constitutional scrutiny.

-

The Tun Daim I Knew.

You have enemies? Good … That means you’ve stood up for something, sometime in your life. [Winston Churchill]

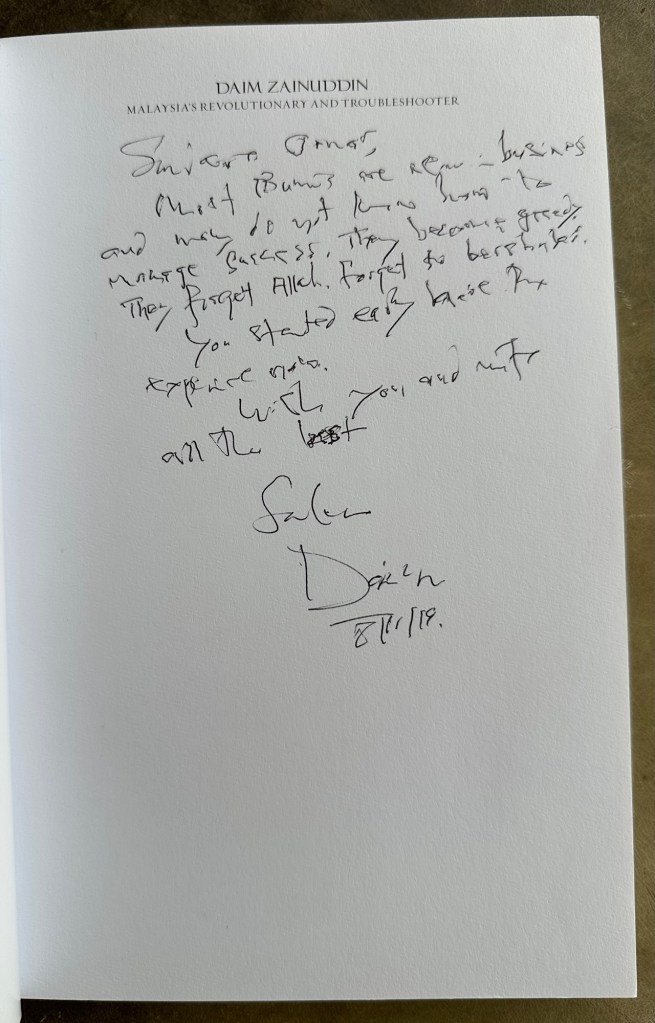

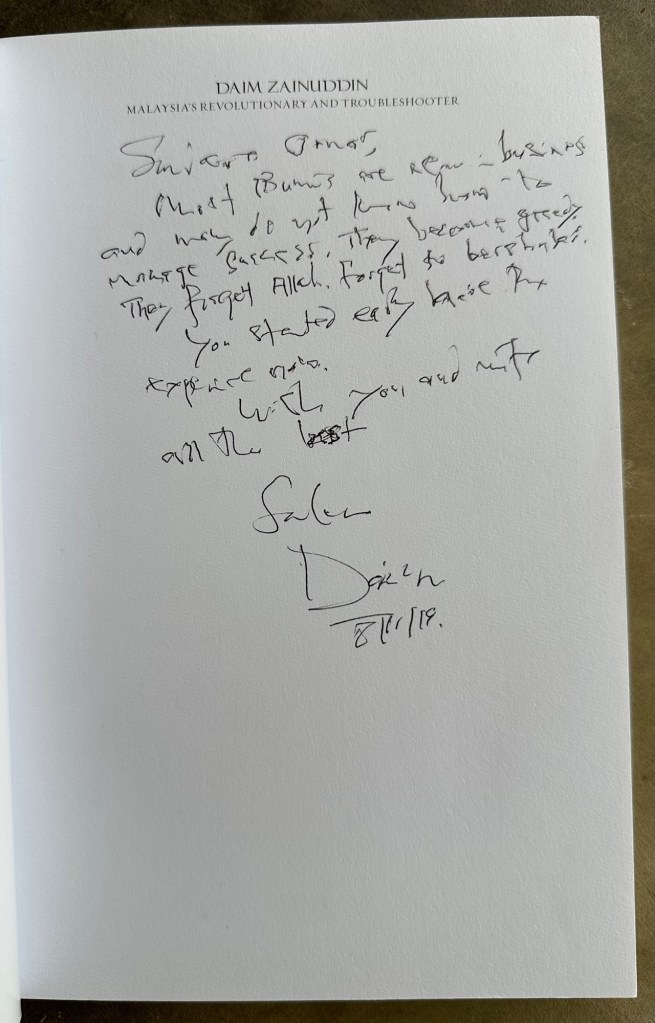

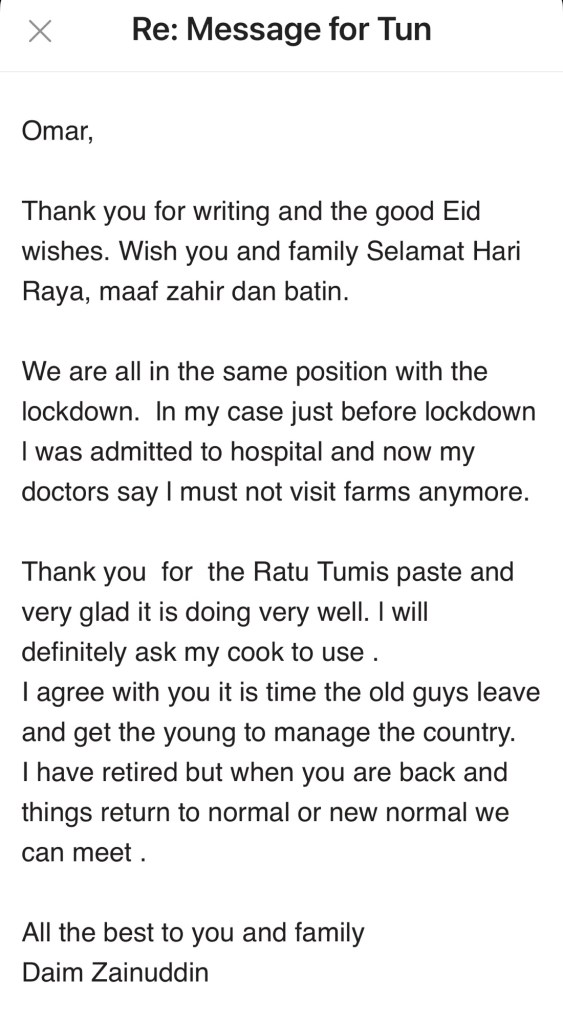

Saudara Omar, Most bumis are not in business and most do not know how to manage success. They become greedy. They forget Allah. Forget to bershukur. You started early and have the experience now. Wish you and the wife all the best. Salam, Daim 8/11/19. Early yesterday morning, Tun Daim Zainuddin, 86, passed away after a long illness. There will be much ink spilled about the man in the coming days.

Most if not all of the English business media and blogs will be unflattering. Daim will be eulogised as a fabulously wealthy former Finance Minister and long time Treasurer of UMNO. Having long been vilified, many – including those currently occupying the commanding heights of business and government – would rather he be remembered a villain. For those who recall their history, echoes of Tun Tan Siew Sin and Tan Sri Tan Koon Swan linger heavily in the air.

Few will be willing to mention let alone acknowledge what Tun Daim was at his very core: a shrewd, careful and fearless businessman whose first love was making money. He made money for himself, for the political party he once belonged and for his country – perhaps in that order too. Like any good businessman everywhere, he was sought out by the powers that be and was ultimately roped into government not once but twice. Which inevitably attracts more attention and jealousy. Just ask Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. But that’s life.

I first met Daim when I was still in university in the early nineties. He had just left government by then after his first stint as Finance Minister. I was running a student magazine and sought an interview with this elusive, diminutive wizard of a man. The interview went well, he was surprisingly candid. When I asked about his time in government, his reply has stuck with me until this very day: “Omar, you cannot be a good businessman and a good politician at the same time. A good businessman has no business being popular. A politician is a failed politician if he is unpopular. You must choose what and who you want to be.”

I would see Daim regularly over the years. His office at Wisma YPR would call every now and then to say Tun would like a chat. He had a habit of going through the mountain of papers on his messy desk while in conversation, putting his pencil down only when he wished to make an important point. We talked mostly about world events, the global economy, market cycles for all kinds of commodities, the mood of the business community and to me most interestingly, his adventures doing business abroad, particularly in Africa and Eastern Europe. Outwardly, he was a shy man of few words, but in private he was a man of the world and enjoyed a good debate (and a well-told joke!). Our chats would often last past the hour. He has never once offered me a drink or kuih. That’s Daim for you. Business-like, inquisitive and matter of fact. But he would also end by thanking me for coming by and that I should not hesitate to reach out.

And reach out I did one particular time shortly after I started working at a global MNC. I had been nominated by the UNDP Malaysia office to represent the country as a delegate to the 50th Youth Commemorative Assembly of the United Nations in New York. The UN would pay for my accommodation but I would need to get to New York on my own dime. I promptly shared this good news with my departmental boss who was good enough to allow me to take days off but said the company would not cover my airfare. So I rang Mei at Daim’s office and explained my predicament. The return call was swift: Tun will pay for your return flight to New York on economy (but of course). The company ended up paying for my ticket when they learned that Tun Daim would have been my benefactor!

Through the decades, our paths crossed intermittently but always at critical junctures. He was instrumental in my decision to join McKinsey. On another occasion I declined his offer to serve in a senior political role, reminding him of his own words to choose between politics and business. It was a fortuitous decision as Daim stepped down for the second and final time in Cabinet less than two years later. He continued to do serious business here and abroad. I was content to run my own strategy consulting and private equity firms. We travelled together on occasion in his private jet (sans cabin crew!)

In a world now where successful Malays are to be regarded as cronies or crooks, Tun Daim was to be its chief architect and poster boy. His razor sharp instincts and business acumen that led him to become a valued and trusted confidante of presidents and prime ministers, would need to be obscured and preferably erased. His fault was to be Malay and fabulously wealthy – a feat considered genetically impossible. He was Finance Minister for nine of his eighty six years and some will want those years to define the totality of his existence. I pray and hope not.

In the thirty odd years I have known this quiet enigma of a man, he has touched the lives and careers of so many promising young Malaysians. This enduring commitment to the future of Malaysia will be one of Tun Daim’s most important legacies.

May Allah have mercy on his servant Allahyarham Daim bin Zainuddin for He alone is all knowing and the ultimate arbiter of all things.

Saudara Omar, Most bumis are not in business and most do not know how to manage success. They become greedy. They forget Allah. Forget to bershukur. You started early and have the experience now. Wish you and the wife all the best. Salam, Daim 8/11/19.

-

Podcast: My Career Mosaic

Generative AI & Large Language Models are radically transforming the lens through which we view our world.

Narratives are being reshaped and sharpened in ways previously unthinkable. This example had a single input: my LinkedIn profile.

The output is incredibly flattering.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.