A trade agreement that preserved survival, constrained sovereignty, and quietly reshaped the foundations of our political economy

Malaysia’s new trade agreement with the United States was signed to preserve survival, yet its clauses reach far beyond tariffs and exports. It binds us into America’s orbit abroad while quietly reshaping the levers of our political economy at home. History may record it less as a trade pact than as a bargain that altered Malaysia’s future options.

The Context: Trump’s Tariff Shock

In April 2025 President Trump imposed a blanket nineteen percent “reciprocal tariff” on imports from multiple countries. For Malaysia this was not a theoretical threat, since electronics and electrical products make up more than one third of our exports to the U.S., ranging from semiconductors and components to precision parts manufactured in Penang, Johor and Selangor. A tariff of that size would have priced us out of American supply chains almost overnight.

The choice was stark. We could negotiate or suffer. Vietnam and Thailand chose to sign framework agreements that bought them time, while Cambodia, heavily dependent on garment exports, signed quickly to preserve survival. Malaysia, deeply exposed in electronics and engineering, could not afford delay, and hence we signed a hard agreement.

What the United States Secured

The agreement delivers a number of trophies that President Trump can now claim as victories at home.

PETRONAS must purchase approximately USD 3.4 billion of U.S. LNG annually, providing a fixed and recurring demand that anchors American energy exports into Asia.

Malaysia also committed to facilitate around USD 70 billion in job-creating investment in the U.S. over the next ten years. Few trade agreements require a developing country to create jobs abroad rather than at home, yet this one does.

In addition, Malaysia agreed not to ban or quota rare earth and mineral exports to the U.S., and guaranteed no restrictions on rare-earth magnets, thereby assuring American supply-chain access in a sector otherwise dominated by China.

Regulatory alignment was also embedded. Malaysia must fast-track halal certification for U.S. food products, accept U.S. FDA approvals for pharmaceuticals and medical devices, and recognise U.S. auto standards. Restrictions on U.S. broadcasting content are lifted, and American digital services cannot face discriminatory treatment.

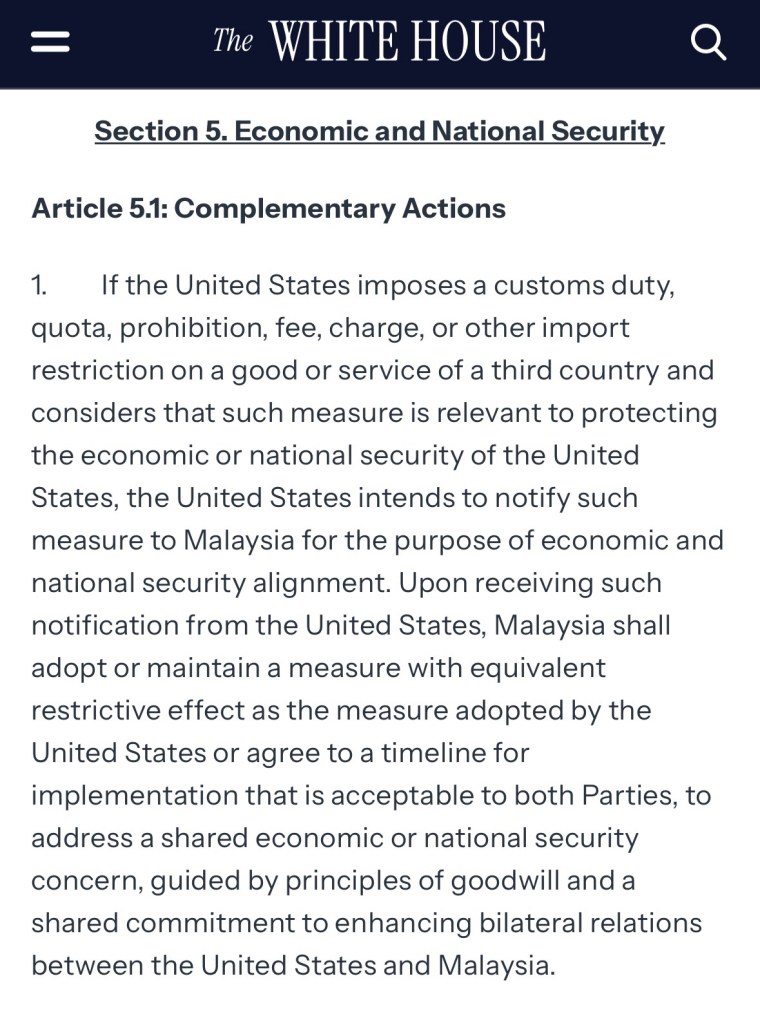

Most significantly, the agreement contains clauses that reach beyond trade. Malaysia must consult the U.S. before entering new digital trade agreements with other countries that might be judged to jeopardise American interests. Malaysia is required to adopt or maintain measures equivalent to U.S. trade restrictions when imposed against third countries. If Malaysia signs a free trade or preferential deal with a country that threatens U.S. interests, Washington may terminate this agreement and reimpose tariffs. These are not commercial provisions alone. They embed Malaysia inside the strategic orbit of the United States.

What Malaysia Preserved

To dismiss Malaysia’s position as weakness alone would be unfair, since there were important defensive wins.

By signing, Malaysia ensured its electronics and engineering exports remained competitive in U.S. supply chains, protecting tens of thousands of jobs. A signed agreement also reassures global investors that Malaysia remains a reliable node in the semiconductor and technology ecosystem.

If PETRONAS embraces the challenge of portfolio LNG trading, juggling multiple supply sources and shipping arbitrage, it could emerge stronger in the long term. Most importantly, Malaysia avoided the worst outcome. In any negotiation with Trump there are only two outcomes. He wins and we lose, or he wins and we also win. Malaysia avoided the first of these.

However we need to be clear-eyed and honest about who exactly are the winners and losers both within and beyond Malaysia, and equally about the likely winners and losers in the years ahead as this agreement is enforced.

The Strategic Price Paid

Survival came at a cost.

Malaysia now carries binding obligations on LNG imports and outward investment flows. At a time when our own economy needs capital, significant sums have instead been committed to creating jobs in America.

More serious is the narrowing of our sovereign space. Consultation requirements limit our freedom to enter digital trade deals independently. Obligations to mirror U.S. trade measures tie us to American sanctions and disputes with third countries. The termination clause places Malaysia’s future free trade agreements under a U.S. veto threat. Commitments on critical minerals guarantee American access and weaken Malaysia’s leverage in resource diplomacy. Regulatory alignment narrows our room to strike alternative models with China, ASEAN or the Middle East.

The regional dimension also matters. By signing hard during the ASEAN Summit while Thailand and Vietnam kept their options open, Malaysia fractured the symmetry of ASEAN bargaining. Washington now points to Malaysia as precedent, asking other states: “They agreed – why not you?”

Finally, there is the risk of over-payment. If Thailand and Indonesia later conclude softer deals, avoiding LNG obligations, resisting sanction clauses and retaining digital autonomy, Malaysia will look like the country that conceded more and did so too early.

A Quiet Reset of the Bumiputra Agenda

Beyond sovereignty, the agreement also reshapes the space in which Malaysia’s race-based economic architecture has long operated. Since the 1970s, Bumiputra-first policies have relied on licensing discretion, regulatory gatekeeping, and preferential access to contracts. By embedding obligations on standards, certification, digital services and market entry into an international treaty, much of that discretion is now constrained.

Malaysia cannot easily reinstate protectionist barriers without triggering treaty violations. Halal approvals must be streamlined. Foreign certificates must be recognised. U.S. digital and broadcasting firms must be given equal treatment. Critical minerals must remain open to American partners. These provisions may appear technical, but together they erode the very levers through which the old order sustained itself.

This is not the abolition of Bumiputra policy. It remains entrenched in education, procurement and contracting. But it is the quiet internationalisation of reform. For decades, domestic politics could not dismantle these preferences. A trade treaty has begun to do so, clause by clause, without a political uprising and without the language of reform.

The Long March Ahead

So was the agreement good? For the United States the answer is clear, for it secured both economic gains and lasting strategic leverage. For Malaysia the answer is narrower, because the agreement was good only in the limited sense that it preserved survival, while strategically it imposed costs that will bind us for years to come.

The deeper test will emerge when Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam finalise their own arrangements. If they are compelled to sign agreements that replicate Malaysia’s clauses, then we will be seen as a first mover who secured stability early. If they manage to escape with softer terms, however, Malaysia will stand exposed as the outlier that conceded more than was necessary and did so too quickly.

In the end, Malaysia signed to protect its factories, but the United States signed to project its power. That asymmetry will not be measured in months, but in decades. It is not a question of who won the negotiation. It is a question of what kind of Malaysia will emerge from its consequences.

This is not cooperation. This is delegation. Article 5.1 binds Malaysia to adopt American measures against third countries in the name of U.S. economic or national security. Even among allies, such an obligation is unprecedented. It does not describe partnership. It describes subservience written into treaty text.