Over the past few months, Malaysia has been confronted with two converging constitutional flashpoints:

A Royal Decree for Najib Razak’s house arrest that was issued but ignored by the executive, and an attempt by the Attorney General to shield Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim from a civil sexual harassment suit on the grounds that litigation would impair his ability to govern.

Both issues invoke fundamental provisions of Malaysia’s constitutional architecture. Together, they raise uncomfortable questions about whether constitutional principles—particularly the limits of executive accountability and the exercise of royal prerogative—are being applied consistently, or selectively.

Two Decrees, Two Outcomes

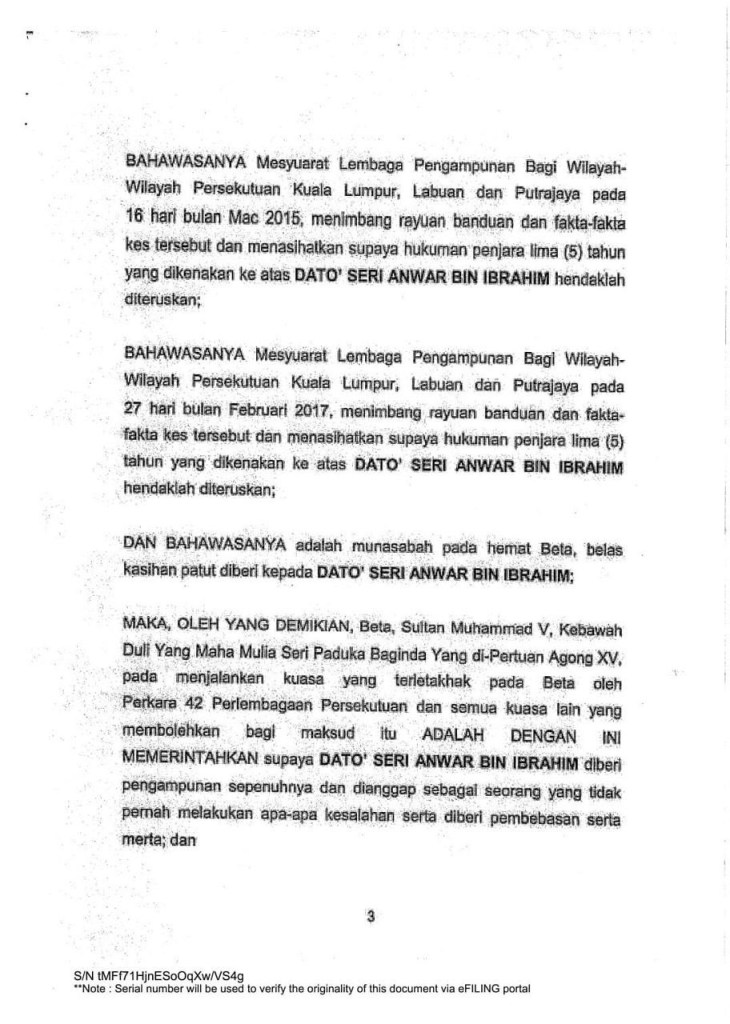

In May 2018, the 15th Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Sultan Muhammad X, issued a full pardon to Anwar Ibrahim following a Pardons Board meeting convened 443 days earlier. The constitutional vehicle was Article 42, which grants the King the power to pardon or commute sentences upon receiving advice from the Pardons Board.

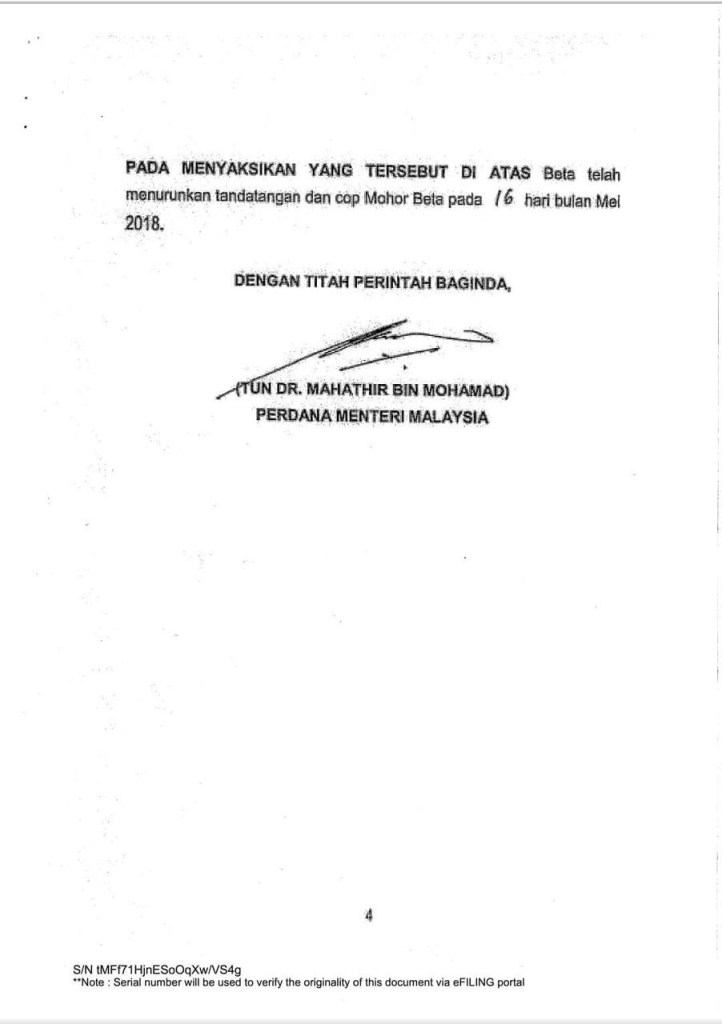

Despite his well-documented personal scepticism, then–Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad signed the Royal Order without delay, giving full effect to the decree. Anwar was released from prison within hours. At the time, this swift execution of the King’s order was widely regarded as a restoration of justice—and a principled act of statesmanship by a Prime Minister who set aside political rivalry to uphold the Constitution.

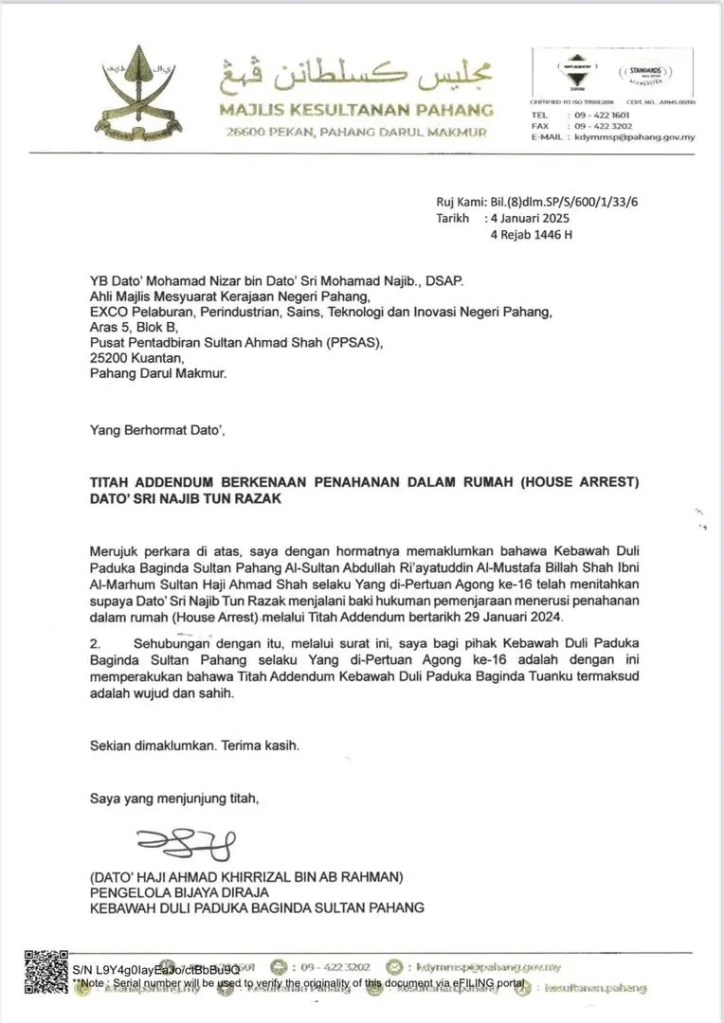

Fast-forward to 2024. The 16th Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Sultan Abdullah, issued a Titah Addendum directing that former Prime Minister Najib Razak serve the remainder of his prison sentence under house arrest—a reprieve, not a full pardon, but one granted under the same provision of Article 42.

As in 2018, this decision came after a validly convened meeting of the Pardons Board. Yet unlike in Anwar’s case, the Titah was met with silence. The Prime Minister’s Office offered no acknowledgment. The Attorney General did not act to implement it. For weeks, the public was told it was mere rumour. It was only after the Pahang Palace issued a formal confirmation that the Addendum’s existence was officially recognised.

This contrasting treatment—same constitutional basis, same royal institution, same executive authority, but opposite responses—demands scrutiny.

The Legal Framework: Article 42

At the heart of both cases lies Article 42 of the Federal Constitution, which governs the Royal Prerogative of Mercy. The provision reads, in part:

“The Yang di-Pertuan Agong has power to grant pardons, reprieves and respites… upon the advice of the Pardons Board.”

That phrase—“upon the advice”—has long been interpreted by courts and constitutional scholars to mean that the King must be advised, but is not bound by the Board’s recommendation. It is not merely a procedural consultation; the discretion ultimately remains with the monarch.

In 2018, this principle was respected. Sultan Muhammad X rejected the 2017 Board’s recommendation to uphold Anwar’s sentence and instead exercised his discretion to pardon. Mahathir, despite personal hesitation, acted in accordance with the decree.

In 2024, Sultan Abdullah chose to exercise similar discretion in Najib’s case—granting a reprieve, not a pardon. But this time, the Prime Minister did not act. No explanation was offered. The Attorney General did not even disclose the existence of the Addendum to the court in subsequent proceedings, leading to a contempt motion being filed against him.

Political Selectivity in Execution

In a widely shared X thread, I asked a direct question:

If your political nemesis could set aside his reservations and implement the King’s order for you in 2018, why could you not do the same for Najib in 2024?

This is not a moral comparison between individuals. It is a constitutional comparison between outcomes.

Both the Anwar and Najib decrees were:

Issued under Article 42, made following a Pardons Board meeting, signed by a reigning YDP Agong, delivered to a sitting Prime Minister for implementation.

Yet only one was acted upon. The other was ignored, and actively withheld from judicial proceedings—despite its clear constitutional standing.

Immunity and the Double Bind

This pattern is made more troubling by a recent move by the Attorney General to apply for a Federal Court ruling on whether Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim should be entitled to immunity from civil litigation while in office.

The claim is that defending a sexual harassment suit—filed by Anwar’s former speechwriter—would impair the Prime Minister’s ability to perform his duties.

The optics are now deeply problematic:

A Royal Decree benefitting someone else is ignored. A civil suit implicating the Prime Minister is deferred. Constitutional discretion is withheld from political rivals but claimed for personal protection.

This is not merely legally inconsistent. It is corrosive to public trust in constitutional governance.

Rule of Law or Rule of Preference?

The rule of law depends on consistency—across time, across cases, and across personalities. When identical constitutional instruments are treated differently depending on who they favour, the appearance is one of selective enforcement. That is damaging not just to the reputation of the executive, but to the institutional credibility of the Attorney General’s Chambers, the Cabinet, and the wider government.

Malaysia cannot afford a system where:

Clemency is implemented for one leader but denied for another, Royal orders are honoured when politically expedient and disregarded when they are not, a sitting Prime Minister is shielded from civil accountability while others are denied relief from incarceration already approved by the monarch.

A Final Note

Malaysia’s constitutional monarchy is not ornamental. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong, acting within his constitutional powers, represents a stabilising force between institutions. Article 42 is not a ceremonial device; it is a substantive legal mechanism that, when used, must be respected—no matter who benefits.

If one Royal Decree can be ignored, and one civil suit evaded, what remains of the rule of law?

The true test of a constitutional democracy is not how power is used when it suits us—but how power is respected when it does not.

Postscript:

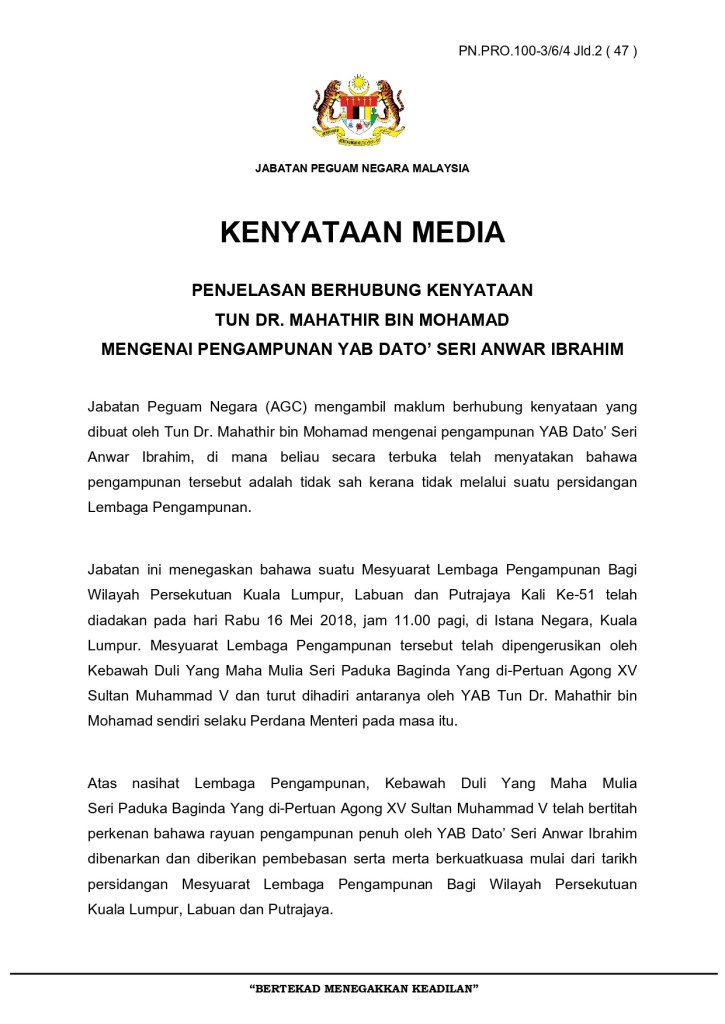

On 3 June 2025, the Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) issued a public statement in response to Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s assertion that the Royal Pardon granted to Anwar Ibrahim in May 2018 was unconstitutional. The AGC sought to correct the record, asserting that a properly constituted Pardons Board meeting did take place on 16 May 2018, and that the Prime Minister at the time, Dr Mahathir, was in attendance.

However, while the statement may appear to settle the issue at face value, a closer examination reveals several critical ambiguities with constitutional and procedural implications—particularly relating to quorum, composition, and the role of the Attorney General.

1. AGC Affirms the Existence of a Pardons Board Meeting

The AGC’s statement confirms that a Federal Territories Pardons Board meeting was convened at Istana Negara at 11:00 AM on 16 May 2018, chaired by His Majesty Sultan Muhammad V, then the 15th Yang di-Pertuan Agong. It asserts:

“Mesyuarat Lembaga Pengampunan tersebut telah dipengerusikan oleh Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong XV Sultan Muhammad V dan turut dihadiri antaranya oleh YAB Tun Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad sendiri selaku Perdana Menteri pada masa itu.”

This line, while affirming Mahathir’s presence, stops short of confirming the attendance of any other members, nor does it specify in what official capacity he attended—an issue that has legal ramifications.

2. Article 42(10) and the Requirement of Quorum

Under Article 42(10) of the Federal Constitution, a Pardons Board meeting must include at least three members, not including the Yang di-Pertuan Agong:

“The presence of three members shall be necessary to constitute a quorum.”

The members required under Article 42(4)(aa) are:

The Attorney General (ex officio), The Minister responsible for the Federal Territories, and Up to three members appointed by the YDPA.

The AGC’s statement does not disclose whether any of the appointed members or the Attorney General were present in person. The lack of such information raises legitimate doubts about whether constitutional quorum was satisfied.

3. Ambiguity Surrounding the Attorney General’s Attendance

The AGC further states:

“Bagi tujuan mesyuarat tersebut, Peguam Negara juga telah memberikan pendapat bertulis mengenai perkara itu selaras dengan Fasal (9), Perkara 42 Perlembagaan Persekutuan untuk pertimbangan Lembaga Pengampunan.”

This suggests that the Attorney General may not have attended the meeting physically, instead submitting a written opinion as permitted under Article 42(9).

While written advice satisfies the AG’s advisory duty, it does not count towards quorum unless the AG was physically present as a Board member. This distinction is crucial: an advisory function does not substitute for membership presence for the purpose of quorum.

4. Was Dr Mahathir Acting as the FT Minister?

Another unresolved question is whether Dr Mahathir held the portfolio of Minister for the Federal Territories at the time of the meeting.

He was sworn in as Prime Minister on 10 May 2018, but no other ministers were appointed or gazetted until 21 May 2018. Therefore, on 16 May, he was the only formally appointed member of the executive.

If Mahathir was not officially gazetted as holding the FT Ministry, his presence may not have satisfied the constitutional requirement under Article 42(4)(aa). The AGC statement does not clarify whether he held or acted in that role.

5. Legal Consequences of the Uncertainty

The constitutional legality of the 2018 pardon hinges on whether:

At least three Board members (excluding the YDPA) were physically present; The AG’s written advice alone sufficed, or whether physical presence was necessary; Mahathir’s attendance was in a qualifying constitutional capacity; Any appointed members of the Board were present at all.

If the quorum was not met, a potential argument arises that the YDPA relied on the advice from the earlier Pardons Board meeting of 27 February 2017, where Anwar’s application was previously considered. In such a case, the 2018 meeting would be treated not as a deliberative meeting, but as a ceremonial or administrative moment to formalise the YDPA’s change of heart—a discretionary act clearly within the monarch’s powers under Article 42(1).

However, the AGC’s refusal to clarify the full attendance list weakens the robustness of its constitutional defence and leaves the legal narrative inconclusive.

6. Broader Institutional and Political Ramifications

While this controversy may appear historic, it has immediate relevance to current debates—particularly surrounding the 2024 Titah Addendum involving Najib Razak. Critics will now argue that:

Both pardons involved discretion exercised by the YDPA, following Board advice; The Anwar pardon was implemented immediately, despite procedural doubts; The Najib clemency decree has been left unimplemented, allegedly on the basis of procedural ambiguity.

This creates a perception of inconsistent treatment of royal clemency decisions depending on political alignment.

Until these ambiguities are resolved, the procedural regularity—though not necessarily the legal validity—of Anwar Ibrahim’s 2018 pardon remains open to constitutional scrutiny.